Lee had something truly unique in store for Meade that day. Once again, there are no records or precisely when or how Lee had concocted this tactic. On the morning of Day 3, Lee again diverted from his normal command policy. He by-passed his Chief of Artillery, BG William Pendelton – in whom he had no confidence – and summoned Longstreet’s Artillery Battalion Commander, COL Edward Alexander. It would have been completely out of character for him to do so outside of the presence of Longstreet himself, so they were likely all together. But once again, Lee was discussing details of an operation with a subordinate commander. Longstreet felt by-passed!

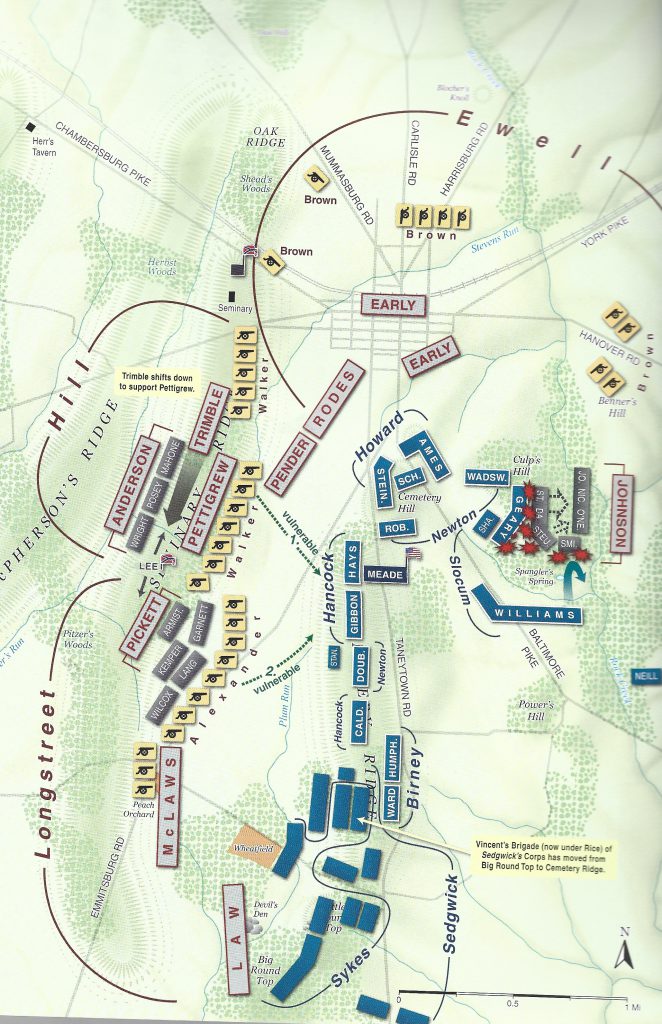

Lee wanted Alexander to muster every cannon he could find and to emplace them where they could bombard the center of Hancock’s Second Corps. When all was said and done, there were about 120 barrels pointed at Hancock. Since the barrage was to take place at about a mile’s distance, every solid iron cannon ball and exploding shell was assembled as well. The majority of the cannons were aligned along the top of Seminary Ridge, but the line included the Peach Orchard knoll (Sickles was right!).

[Editorial Note: One has to ask whether placing these guns on the ridge on Day 2 might have affected the outcome of the late afternoon attacks by Anderson or perhaps even the routing of Sickles’ Corps. Granted Lee had a limited amount of ammunition, but this was an effort to win the war!]

Beginning about 1PM, those cannons opened fire most aiming at a clearly visible point on the horizon: a copse of trees [1]. COL Alexander had doubts that he could accomplish the task Lee handed to him of clearing the Union artillery from the area around those trees. At the far north of the artillery line, the cannons were aimed into the cemetery with the task of depleting the ability of the Union’s concentration of cannons there from responding to the impending infantry charge. From the area of the orchard, the artillerymen aimed at the Union cannons that might be brought to bear from Little Round Top.

It is not hard to do the math. A well-trained artillery team could fire a minimum of 3 rounds per minute (a few even faster). 120 cannons could throw 3-4 rounds per minute = over 21,000 rounds in an hour. COL Alexander had done his job well in ranging the distance to the Union line and determining the flight time for which to set the fuses on the exploding shells. Unfortunately, due to the inferior gunpowder in those fuses they were burning too long and the shells were flying too far before exploding.

Another problem for Alexander, Pickett, Longstreet and Lee was how to know if and when the barrage had accomplished its purpose. As soon as the Confederate a cannonade began and the Union batteries began to answer, the entire valley filled with the smoke generated by the black powder. Neither side could actually see the other. One answer would have been to place an observer in the Seminary cupola. He would have had a reasonably unobstructed view of the Union line. The problem would have been the time any messenger would take to deliver any suggestions he had to alter the fire. In reality, at least, he would have been able to tell COL Alexander that his shells were flying long and have him shorten the fuse times. But this did not happen!

COL Alexander was being placed in an almost untenable position. He knew that in order to accomplish Lee’s vision of clearing a path for the infantry, he would have to expend an enormous amount of ammunition. As the bombardment approached one hour, he noted that the rate of fire of some of the guns was decreased. Not only were the men tiring, but as ammunition ran low they slowed their firing rate. There was more ammunition to be had, in the logistics reserves, but they were too far to the rear. It could not have been brought up fast enough to continue the barrage. Plus he wanted to save some of the available ammo to use in direct support of the infantry advance. The reserve ammo would have to wait for any follow-on action.

On the Union side, the sound wave that broke over their line as the 120 cannons fired in sequence then almost simultaneously, was startling to say the least. Throughout the morning there had been some rumblings of cannon fire off to the east on the far side of Culp’s Hill, but the western side of the line had been quiet – almost too quiet. Even skirmisher activity had been low.

Behind the low stone wall, some Union men hugged the ground, noses in the dirt. Others lay on their backs trying to get a glimpse of the shells as they flew in. To their amazement, most of the shells were exploding beyond them. The infantry riflemen were being spared but the wagon masters, black smiths, cooks and medical personnel were taking a beating. Perhaps the worst part were the exploding caissons. These ammunition carriers were usually parked a bit to the rear of the artillery batteries in an effort to keep them out of the line of fire. At Gettysburg, that meant that most of them were on the reverse slope of the hill and out of sight. But this placed many of them in the path of the over-flying shells. The Union artillery may have lost as much ammo to exploding wagons as that that they fired! The horses, too, were falling prey to the Rebel fire. Many frightened and wounded horses were running free – running amok – behind the lines.

As luck would have it, LTC Chamberlain’s 20th Maine Regiment had been moved earlier that morning from their perch on Big Round Top where they had spent the night guarding that line of approach. They was assured that they were going to a ‘safe place in the center of the line’. As it was they were just a short distance from the copse of trees.

Lee had no way of knowing it, but that copse of trees [1] was serving as LTG Hancock’s HQ area. He and his command staff had to scramble to get out of the way of the first volley of shells. Hancock spent the rest of the barrage, riding up and down the line trying to calm his men. Meade’s HQ in the Leisiter House just below the cemetery came under heavy fire. Several horses were killed in the front yard and the house and fence took a number of hits. His staff finally convinced him that he should shift his HQ closer to Culp’s Hill for safety. But fearing that messengers would not be able to find him, he moved back as soon as the barrage lightened.

[1] Historians have begun to doubt the role that this formation played in this crucial battle. A few suggest that its importance wasn’t even raised until decades after the battle and that it was actually Zeigler’s Grove that Lee was targeting, but by the mid-1880s those trees had been logged out and ‘the copse’ was touted as the focal point of Pickett’s attack.