Every war, every battle has its heroes and acclaimed leaders; they are also often unsung heroes who get lost in history, so too, at the Battle of Gettysburg. Anyone who knows anything about the Civil War can identify J.E.B. Stuart as Robert E. Lee’s Cavalry Commander.

In that era, it was the job of the cavalry to ride far ahead of the main force to scout the terrain and to fix the position and strength of the enemy in the area. During Lee’s incursion into Pennsylvania his infantry was advancing up the west side of a small mountain range. Stuart had led his cavalry up the east side. Physically separated, he could not communicate with Lee. Therefore, he could not do his job! His counterpart for the Union Army was BG John Buford.

Buford is the either one of the unsung heroes of Gettysburg or someone who should have been courts martialed for insubordination. I oscillate between these two opinions. His orders of the day were to locate the Army of Northern Virginia; a rather straightforward task for an experienced cavalry commander. If they were in the area he should be able to locate upwards of 50,000 men marching through the countryside. He’d locate them – or maybe not – and be back at Reynolds HQ at Emmittsburg in time for supper.

Buford reportedly arrived near the city of Gettysburg sometime on the morning of June 30. Almost simultaneously his advance scouts arrived from two directions. One reported that there was no sign of Ewell’s Corps approaching from the north.

Having ridden up the Emmittsburg Road, Buford is said to have ridden to the crest of Cemetery Hill just south of the city. He then rode west to the highest point in the area: the Seminary building at the north end of Seminary Ridge. From the cupola of that building he gazed out over the entirely flat terrain of fields and pastures to the north and west.

For those who even knew that the small city of Gettysburg existed (popn about 2400), it was a place that people went through not to! Gettysburg’s claim to fame was that it was the crossroads; a hub of roadways leading to each of the major cities in the area. Gettysburg was but a way-point on one’s journey between those cities. Buford was an astute tactician, that was one reason he was such an effective cavalry commander. He immediately determined that the city of Gettysburg was of no military value. He was, however, impressed with the series hills to the south and west of the city that could be a strong defensive position and possibly even determine the outcome of a battle.

It is said that from the cupola of the Seminary, Buford spotted a small group of armed men. They had no uniforms that he could discern but they had muskets and were heading west towards a thick stand of trees off in the distance some mile or so away. Buford rightly guessed that these were scavengers. One was leading a cow and the others were carrying sacks. Such small groups were sent out on the fringes or ahead of a unit to secure supplies. That cow would be in the stew that Lee’s men would eat that night. At this moment, Buford had accomplished his mission for the day! Lee’s vanguard was just a short walk west of Gettysburg. At this moment, he should have mounted his horse and led his men back to Reynolds’ HQ.

To Buford the plan was all but obvious; he had to delay the advance of Lee’s forces until the Union Army could arrive. That force was only a few hours march to the south in Emmittsburg. It could arrive in time to assist him if he simply sat in the way of Lee’s advance. By the end of the next day (1 July 1863) the Army of the Potomac could be occupying the hills to the south and west of the city that would determine the fate of the battle. Hooker is said to have stated that Pipe’s Creek was “a good place to win a battle”. Buford was thinking that Gettysburg was “a good place to win a war”!

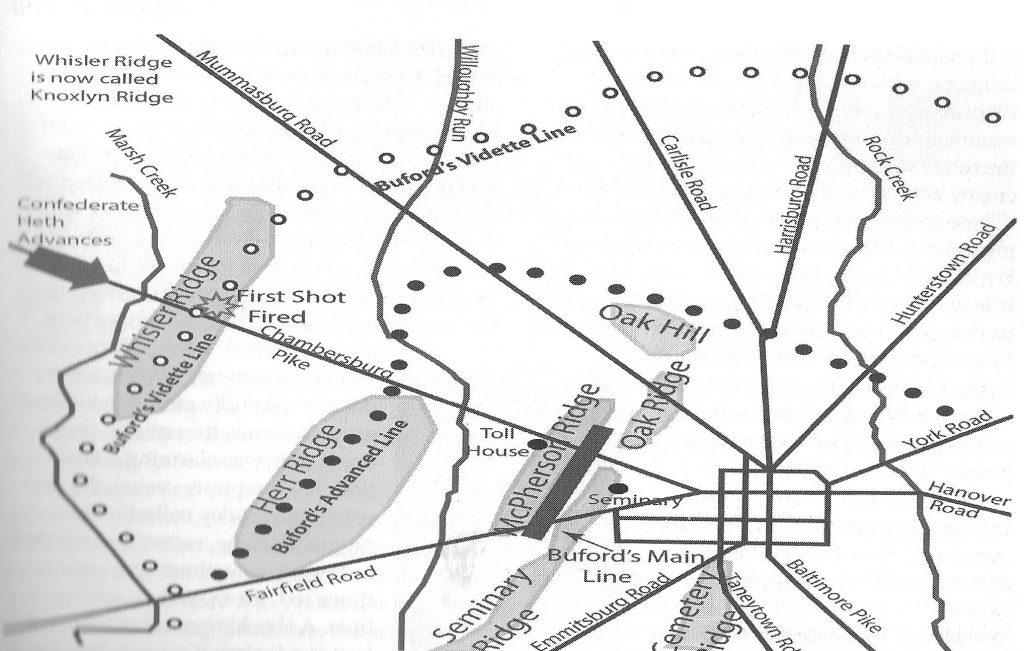

His plan came together like a drawing being completed. He positioned his 3-gun artillery battery on a hilltop near the Seminary and told them to range the road from Cashtown where it emerged from a tree line. He then positioned about 300 dismounted cavalrymen along Willoughby Creek and behind hillocks, stone walls and split rail fences across the path of the advancing Rebel Army. He dispatched a small force to the north to watch for Ewell’s arrival. He’d deal with them when the time arrived. His main objective was to delay Lee’s main force.

We need to stop and consider what he was doing. He was a (mere) Brigadier General in command of a moderately small force. He was concocting a plan that was far in excess of any orders that he had received. He was literally “drawing a line in the sand” and demanding that his Commanding General support his decision to engage the enemy without orders to do so. Such was his confidence in himself, his men and his plan that he simply knew that his commanders would support him. If not, within 24 hours he and his men would be dead or prisoners.

Was Buford’s plan to invoke an ambush, a brilliant tactical maneuver, OR did his actions border on insubordination and courts martial offenses? In short, his orders from MG Reynolds were to scout ahead and try to locate the position of Lee’s army. We will discuss alternative outcomes in later ALT HX sections of this website [see Section 23-24].

Buford had reportedly accomplished this mandate before noon. He could accurately place the vanguard of Lee’s army a few miles west of Gettysburg on the Chambersburg Road.

Everything in the cavalry manual of operations of the era should have compelled him to return to Emmittsburg and report his findings to Reynolds.

Instead, he concocts the insane scheme that his 3300 men would ambush the entire Army of Northern Virginia and attempt to hold them in place until re-enforcements – in the form of Reynolds’ First Corps — arrived to save him. Granted, he had the element of surprise on his side and in sheer fact that is what probably saved his command and his life.

He seemed to have a profound trust that his commander, Reynolds, would accept his decision and respond appropriately by moving to his aid at dawn on 1 July 1863. Had Reynolds – for whatever reason – not arrived in the late morning, by nightfall, BG Buford and most of his men would have been dead or captured. He had no hope of holding off an assault by Hill’s Corps for more than a few hours.

In a perverse way, his dispatches back to Reynolds and Meade were orders from a subordinate commander to his higher commands to commit to rescue him or risk the loss of his entire command. He really wasn’t giving them much of a choice. He was essentially and unilaterally daring Meade to commit his entire army to a battle at a time and place that Buford alone was setting, not really leaving them much of a choice but to commit major forces to rescue him.

IOW, he –a mere Brigadier General – had usurped the authority of the Commander of the Army of the Potomac and committed him to a battle he never anticipated!

In all reality, Meade was still anticipating that he would consolidate his seven corps at Pipe’s Creek to defend the supply hub at Westminster.

Granted, Buford was an excellent cavalry officer and he had a good eye for the terrain. His assessment of the series of contiguous hills south of Gettysburg as a “good place to win the war”, was agreed to by each successive Union general who arrived on the scene. But this still did not give him the right to commit the Army of the Potomac to a battle at Gettysburg on terrain that no one but he had assessed.

When he sat on the grounds of the Seminary and wrote out his mid-afternoon dispatches to Reynolds and Meade, he was in effect exceeding his orders and acting as the army commander. Meade had no direct knowledge of the terrain features that Buford had observed and was initially reluctant to commit his entire force to that area. For this reason, he had dispatched LTG Hancock to Gettysburg at about noon on 1 July with a mandate to report on conditions, terrain and the overall military situation. Based then on Hancock’s (not Buford’s nor Reynolds’) report, Meade decided to commit his seven corps to converge there.

By the time Hancock arrived on the scene, in the mid-afternoon, Buford had already been relieved by Reynolds (who was by then KIA). Hancock quickly assessed the terrain and the military situation and agreed that this was a highly defensible position. He then turned his full attention to rallying the Union troops as they straggled back to the Gettysburg cemetery and establishing a defensive line anchored at that cemetery.

It was as a result of Hancock’s reports that Meade decided to commit his entire force at engage Lee at Gettysburg. Reynolds had been killed in action within an hour of his arrival. He had had no time to inform Meade of any reaction to the terrain or situation. Buford’s glowing accounts were considered but not decisive in Meade’s decision. So it was only after Hancock’s reports that agreed with Buford’s that Meade decided to fully engage.

Despite the fact that the Union forces had been routed off the battlefield on that day, Hancock agreed that a spirited defense could be mounted at Gettysburg and that from there the Army of the Potomac had a good chance of defeating Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. The overwhelming dominance of the Union over the Rebel forces over the next 48 hours seemingly vindicated Buford’s actions that overstepped his boundaries and negated any attempts to hold him accountable for his insubordination and failure to follow his simple orders of the day.