As the shock of the attack and the subsequent carnage in the valley between the two ridges began to subside, Meade had some decisions to make. Did he need to reinforce Culps Hill or could the Twelfth Corps hold? He was just now learning of the cavalry clash that was taking place to the east. Could the Union Cavalry hold against the infamous JEB Stuart? Or would he soon be fighting off another attack near the Baltimore Pike?

Some of his Corps commanders were pestering him with a request to counter-attack in the wake of Pickett’s defeat. Was not Lee at his most vulnerable? Leading this group was LTG Sedgewick whose Corps had yet to engage the enemy. But remembering the huge number of cannons that Lee has placed on Seminary Ridge, Meade was not about to send his men across that same valley — now strewn with dead and dying. He would wait to annihilate the Army of Northern Virginia another day! His men had won two magnificent victories. But after three days of carnage, everyone needed a break. Meade was pretty sure that he understood the organization and strength of Lee’s Army. At this point, it had to be fairly well devastated. He truly doubted that Lee had anything left to throw at him. He fully expected that Lee would now be forced to slink back to Virginia. But he couldn’t be absolutely sure that the cunning Lee didn’t have one last battle in him. He cautioned his commanders to have the men eat and rest but to wait to see what tomorrow might bring. It was after all, Independence Day 4 July 1863! Recovery of wounded and the tending of prisoners went on throughout the night.

=============================

Unlike on Day 2, Lee sat on Traveler and watched the slaughter taking place in front of him. Had Longstreet been correct? Should he have stayed to fight or should he have by-passed Gettysburg to attack elsewhere? It was too late for second guessing; his army was completely devastated. He had no choice but to order the long journey south. He summoned BG John Imboden and gave him orders to begin to load the injured who could be moved into wagons. Under cover of darkness, Imboden would led that wagon train back along the same path that they had taken north. He and his men had been so hopeful then! The only hope left now is that his men would survive the journey. Would Meade attack as he departed? Could JEB Stuart protect his convoy of wounded?

===============================

Meade called a War Council on the evening of 3 July, the main question be put before his commanders was “Should they attack as Lee departed?” His staff was about evenly split. He did not favor splitting his forces into two columns. If he was serious about stopping Lee, he’d had to do just that. One portion would harass the departing Rebels. The other would race south as fast as possible to try to cut them off at the Potomac. It would be a classic hammer and anvil tactic. But in the end, he vetoed any suggestion of a follow-on attack and decided to accept the victory that Lee had handed to him and to withdraw back towards WASHDC. His primary allegiance was to protect that city. Destroying Lee was secondary.

He did agree to allow his cavalry to both pursue and try to race ahead of Lee but that was the limit of his response.

Buford returns:

Having initiated the ambush on Day 1, Buford’s Cavalry Regiment withdrew hours later quite depleted. His men had fought a very unconventional battle for that era. Thinly spread over about 2 miles of terrain, they laid prone behind any hill or obstacle and fired their carbines into the massed Confederate units. But they were decidedly outnumbered and suffered a considerable number of casualties before they were relieved by the Union First Corps.

They did, however, withdraw in good order as each was relieved in place. They gathered at the foot of Cemetery Hill in the pre-arranged rally point and withdrew down the BALTO Pike. GEN Meade subsequently assigned Buford responsibility for guarding the left (southern) flank of the Pike against Stuart’s marauding Rebel Cavalry. There they quietly re-constituted their strength with replacements.

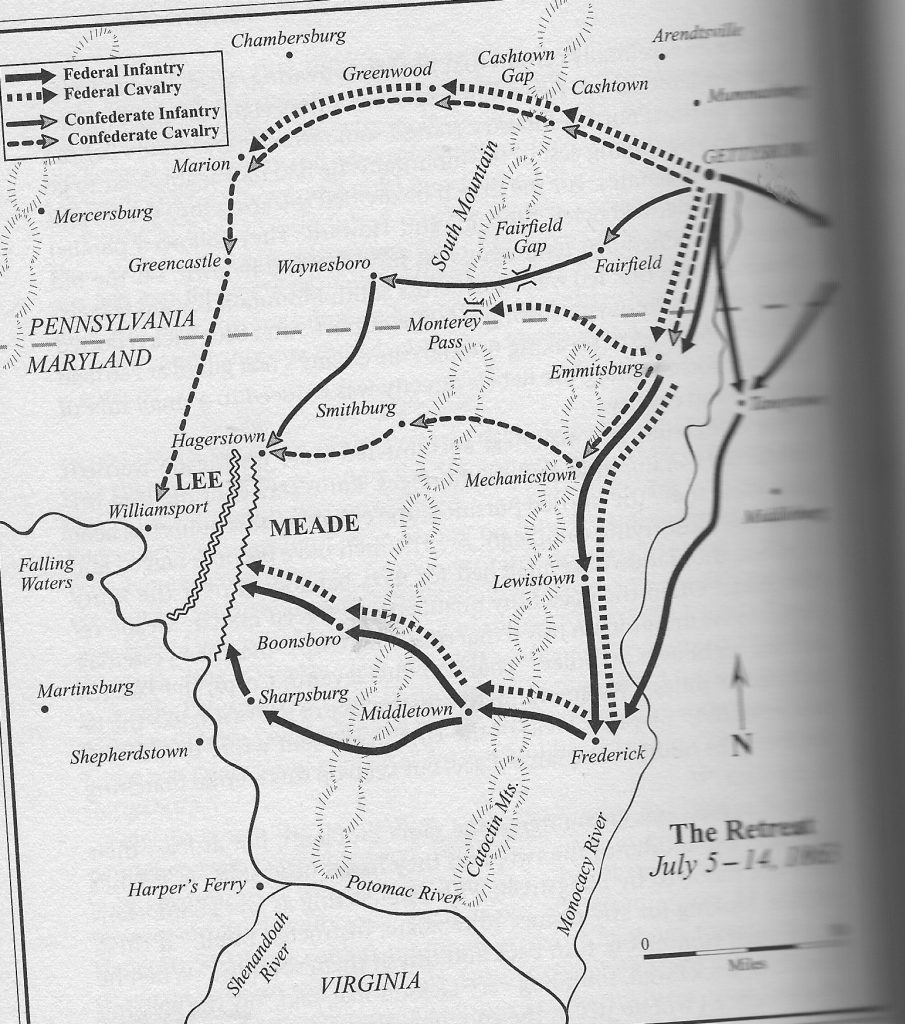

Taking great satisfaction in the major victory he had won over the past three days, Meade was reluctant to squander his army in any hasty moves. Lee had begun his withdrawal late in the evening of Day 3, but those movements were blocked from Union view by Seminary Ridge. A few of Meade’s Corps Commanders urged him to attack the depleted Confederate forces that were occupying that ridge, but Meade did not want to risk a re-run of Pickett’s attack or Fredericksburg by switching from defense to offense. He preferred to wait until Lee’s strategy was clear before reacting. Hence it was Sunday July 5th before he dispatched cavalry elements to attempt to locate Lee’s main force. Since Ewell’s Corps was the easternmost, it withdrew last and so became the rear guard. It was this troop movement that took place under the eye of the Union that convinced Meade that Lee had committed to withdrawal and not further battle.

Despite their overall victory, Meade’s force was also severely depleted. Like Lee, he had lost many of his senior leaders down to the Regimental level. Also, although the situation clearly called for it, he was reluctant to divide his army into separate attack units. Finally he decided, one Corps was sent marching towards Hagerstown. Two others took a longer route south on parallel routes, planning to meet at Middletown and then proceed west towards Williamsport where Meade correctly guessed Lee was headed as his crossing point on the Potomac River back into Virginia.

Faster moving Union cavalry units raced ahead to locate and harass the Rebel advance. The newly reconstituted brigades under BG Buford were among the first to arrive in the Williamsport area. What they found surprised them greatly. The first of Lee’s forces to depart Gettysburg and therefore to arrive at Williamsport, was commanded by an Engineer Officer named Imboden. He had dispatched infantry and artillery units to move ahead of the wagon train of wounded soldiers he led and to erect a hasty defense on the left (east) flank to protect the crossing point. They did a masterful job of using the available terrain to place nearly two-dozen cannons along a north-south line of trenches. Upon arrival at the river, he re-enforced that line with every teamster and ‘non-combatant’ he could muster and arm. He had about 2500 men manning the defense. The Union cavalry numbered no fewer than 3500, but they were loathe to attack into a fortified position. Unknown to them, as well, a wagon train of artillery ammunition had crossed the river to resupply the Rebel force.

Over the next few days, there was a quiet stand-off between the Union cavalry and the Rebel defensive force. During that time, the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia made its way into the Williamsport area. One of the last of those units was Heth’s division of A.P. Hill’s Corps. In one final humiliation of Heth’s was the victim of confusion or misunderstanding among the Rebel Commanders. He thought that elements of Stuart’s cavalry were positioned between his men and the Union cavalry. Unbeknownst to him, the horsemen he viewed to his east belonged to BG Custer! When they moved to attack, Heth had his men hold their fire for fear of hitting Stuart’s (nonexistent) men. When Custer’s horsemen leapt over the barricades at least third of Heth’s division were mowed down.

Just as Lee’s last units were crossing the hastily prepared pontoon bridge on 13 July, Buford’s Regiment attacked and broke through the lower end of the now under-manned defensive line. The final clash of forces in the campaign was Buford’s Cavalry versus Col. Brockenbrough’s depleted infantry brigade. This unit had suffered major casualties as the left flank of Pickett’s ill-fated ‘charge’. Of those who remained, perhaps 500 were captured by Buford before they could evacuate across the river. All in all, the rear guard was said to have suffered 1500 captured in addition to those wounded and killed as they protected the evacuation.

The overall casualty count for the Union in this campaign was somewhat over 30,000. Taking into account the losses protecting the evacuation, Lee re-entered Virginia with about 27,000 fewer men than he took north. Lee’s losses in dead and captured greatly out-numbered those of the Union whose casualties were mostly wounded – some of whom would rehabilitate and return to their units. But perhaps the greatest losses were among the senior Rebel leadership; losses from which the Confederate Army never recovered,

8b.2 the Final Chase

Following Lee’s massive defeat at Gettysburg, Lincoln was displeased to say the least – livid might be a better characterization – that Meade found a number of reasons why the Army of the Potomac (AoP) should not chase and attempt to defeat the Army of Northern Virginia (ANV) once and for all.

Now in early 1865, Lincoln thought that he had a Commander in the person of Grant who could accomplish what Meade had not. Grant had spent months amassing a huge Union Army on the outskirts of Richmond. This prize had always eluded his earlier choices as Army Chief. But now Grant was moving on the Capitol. He was backed by a huge armada of Navy gunboats and supply ships. However, Lee was holding fast to his promise to protect the government of the CSA.

For months through the winter, he and Grant was at a stalemate aligned against each other in parallel trenches that ran nearly 30 miles. To the south they protected the city of Petersburg and it vital rail links to the south. Grant had been slowly exerting pressure by extending his lines farther and farther north. Forcing Lee to do the same. But Grant had a distinct advantage: he had many more men to man those trenches. Even with the rail link open, Lee was having difficulty moving a sufficient amount of supplies to operate an army. The ANV was short on everything while the AoP feasted. The ANV was holding its own against the constant pressure but barely.

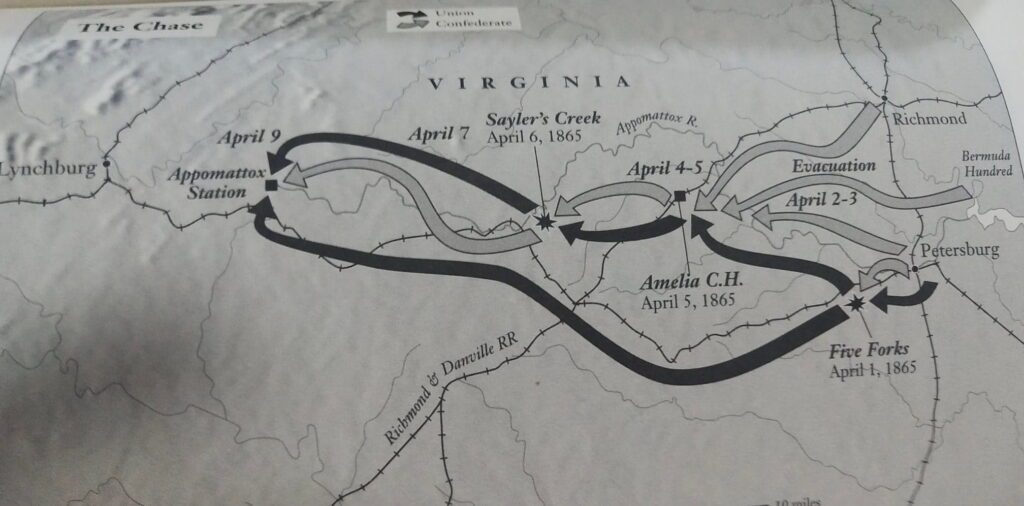

As spring approached, Grant made a move to break the siege. He sent LTG Sheridan to try to seize those rails coming from the south. At the Battle of Five Forks, Sheridan did just that. Lee realized that the time had come to pull back, to abandon the capitol and move west then south to join LTG Johnston’s army in North Carolina. Lee had been planning for this eventuality for some time. He had laid out extraordinarily detailed plans for the evacuation. Primary among this was the positioning of trains with rations along the route of march. But first he needed a head-start on the Union forces. He managed to leave just enough men in the trenches to answer any Union pressure, while the bulk of the ANV slipped passed the city to the west.

It did not take Grant long – about 24 hrs – to punch through the nearly abandoned defenses and enter the now empty city. And them the chase began. Lincoln, himself, was on hand aboard his floating HQ the River Queen at the nearby Port City harbor. It took Grant another 24-36 hours to rouse his troops out of their encampments to pursue Lee. The spring rains were on Lee’s side even if the mud did slow his progress. Grant’s cavalry kept constant pressure on the ANV rear guard not allowing them to fully dis-engage.

While Lee’s haggard men trudged aimlessly west, no food, no sleep, little water, Grant’s cavalry kept the rear guard under constant harassment. But no one was paying attention to Sheridan to the south. He pushed his men hard marching parallel to Lee not stopping to engage. He plan was to get beyond Lee and cut off his escape; he objective was the Appomattox Court House.