Once the decision has been made, getting any army away from the battle scene must be done with as much planning, precision and discipline as any attack maneuver. Every army has a head and a tail. In a retreat, they are in the wrong places. The head and heart of any army is the infantry and artillery. They are closest to the enemy line. Behind them is a vast tail: thousands of wagons; herds of horses, cattle, sheep and hogs. They are also usually blocking the route of escape. How does one get the head away but also protect the vital tail?

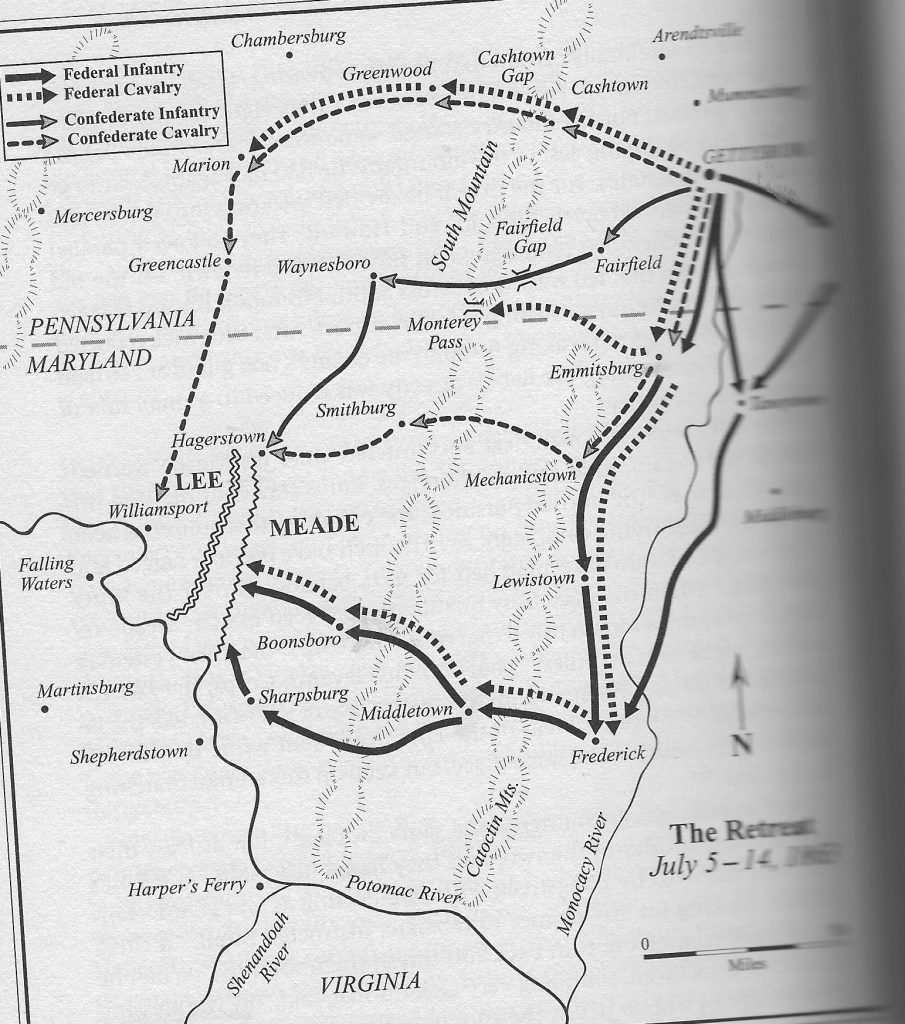

At Gettysburg, Lee had only two means of egress. The shortest was down the road to Fairfield and through the Monterey Pass to the protection of the far side of South Mtn. The other, back the way he came in through Chambersburg, was 20 miles longer; nearly a full days march. He needed to get his entire army to the other side of South Mtn; preferably before the Meade realized what he was doing.

But the road to Fairfield was clogged with wagons and livestock. In the late afternoon of 3 July as soon as he knew he was thoroughly defeated, he sent orders for those wagons to reverse their route of march. Under the cover of darkness in 3-4 July he began to rearrange the chess pieces to get them in position to slip away, while the Union soldiers slept.

Hill’s Corps would move first. It was the farthest west and largely hidden behind Seminary Ridge. It is unlikely that any shift would be detected. Once the route to Fairfield was clear, they would exit south, but only as far as the Pass. There they would establish a protective blocking position allowing Longstreet, then Ewell, to slip over the pass. Once they and all their supply trains were safe, Hill would collapse his position and follow.

Meanwhile, BG Imboden would take the bulk of the wounded and a significant portion of the supply wagons back through Chambersburg.

But first, six full infantry divisions plus Stuart’s cavalry had to disengage from the Union lines. They would do so in stages. If their movement was detected and Meade saw fit to attack, they had to be ready to fight again and not run. Incredibly, it all worked! Except for Stuart. So as not to lose control or contact with him, Lee had sent the most detailed of orders for him to move around to the NW side of the town and then to split his force to provide a heavy rear-guard to both lines of escape. Stuart claims he never received such orders. When he became aware that Ewell was abandoning the east side of the city, he rode rapidly to see Lee face to face. There Lee re-iterated his detailed plan and Stuart (with some reluctance) complied.

As is discussed in Section 8a, once Meade became aware that Lee (not unexpectedly) was indeed abandoning the field, Meade needed to decide to follow or not.

No one ever talks about what it must have been like for tens of thousands of men on the morning of 4 JUL 1863. The three previous days had seen the bloodiest fighting ever in America.

As the sun rose over that now hallowed landscape, thousands wondered what was going to happen next. There is no doubt that the Rebels had carried day 1; after all they drove the Union forces from the battlefield. Yet, it was as if Lee had been a willing participant in the Union plan. As they fell back from the rolling hills west of the city, the Union soldiers occupied the vital high ground to the south. For the next two days, Lee’s men fought on a battlefield they hadn’t sought nor exactly agreed to. They had inflicted heavy casualties on Meade’s 70,000-man army but had sustained more, percentage-wise.

After the disastrous battle of Day 3 known to history as Pickett’s Charge, Lee’s army was spent. Of his three Corps, only Ewell’s was relatively intact. Hill’s and Longstreet’s had both sustained extremely heavy losses. Lee was in no mood nor position to continue the fight, but he was also loath to leave. What if Meade decided to follow him and drive him back to Virginia fighting all the way?

The early morning ground fog masked the carnage of yesterday’s battle but it couldn’t mask the smell. Thousands of bodies still lay in that one mile wide valley between the two opposing forces. Lee was convinced that Meade was going to counter-attack – it’s what he would do in this situation.

A mile away, at Meade’s HQ, some of his staff were arguing for just that action. They thought that they now had the clear upper hand and wanted to end the war on the Fourth of July! But Meade was having none of it. He could easily envision in his own mind a mirror image of Pickett’s Charge with his own men falling by the hundreds in that same field of battle. Sure Lee’s forces were depleted, but they still occupied Seminary Ridge and their artillery was still aligned along its summit. An attack from the south would take too long to develop – much as Longstreet’s actions on Day 2. In short, it would be foolhardy to abandon the high ground that the Union forces now held even with the possibility that the war could be over in hours; it just might turn out that the war would end with a Confederate win!

So as the Fourth of July heat started to beat down on the two armies, they stared at each other across that mile. Neither was inclined to move. They had seen enough killing for now.

In point of fact, Lee had already begun the retreat back to Virginia. A train of wagons carrying the wounded was winding its way along the Chambersburg Pike; the same road they had marched up just days before. They were accompanied by most of Lee’s cavalry as guards. His infantry units were still in place awaiting Meade’s next move. Most were camped to the west of Seminary Ridge, but many thousands were languishing in the woods that covered much of its eastern slope facing the enemy. They waited in the shade for the attack that was never to come.

As the day faded to dusk, Lee gave the order for the units west of the Ridge to withdraw following the wounded. It wasn’t until the evening of the next day that he abandoned Seminary Ridge altogether and pulled out the remainder of his army. They warily began the long march back over the route they had so jauntily covered over the past week. All the while, they expected to hear to roar of Meade’s cannons that would signal his attack on their retreating column. Meade did allow some of his cavalry to head south to interdict the retreat but no major battles ensued and with a week or so Lee was back in Virginia.

For the civilian population of Gettysburg, the war had in one sense just begun. For the most part they and their city had been spared any role in the battle. There had been some fighting at the end of Day 1 as the Union troops withdrew from the northern parts of the battlefield, but they were only attempting to reach the hills to the south. Both armies had recognized that the city itself had no tactical or strategic value.

But now that the battle was over, there were thousands of wounded to be cared for. With Lee’s army in retreat, there was no need for Meade to subject his wounded to a long road trip. While his army withdrew back down the Baltimore Pike, he left his wounded in the city. Most of the churches and other large buildings were commandeered as hospitals.

The second most important task was to bury the dead. Work parties of soldiers and civilians were assigned to this task. Initially, most of the bodies were buried where they fell. Later, contractors would return and exhume them, make attempts to identify them and eventually move them to what would become the first national cemetery. It was in that place that Lincoln would deliver his Gettysburg Address in November.

Gettysburg Day 4 and beyond: The Escape

Following three days of the bloodiest fighting the country had ever seen, both sides were battered and left licking their wounds. Having nothing left to throw at the Union, Lee reluctantly agreed that he had to withdraw – all the way back to Virginia. He assigned BG John Imboden, one of his cavalry commanders, the task of leading dozens of wagons of wounded. On the following day, he and his entire Army joined in the long walk home.

Some might question why Meade allowed Lee to escape. Indeed, a few of Meade’s senior officers urged him to take to the offensive and follow Lee’s Army with the intent to destroy it. But Meade, who had been in command of the Army for about 1 week, was content with his victory – such as it was. He, too, had lost thousands of men in only three days. He was satisfied to withdraw back down the Pike to Baltimore and Washington. He had estimated that it would be quite a while before Lee’s Army of Northern Virginian would be an effective fighting force. He had enough respect for Lee to let him withdraw gracefully.

He did, however, dispatch his cavalry to harass them as they retreated just to remind them of their loss. To make their plight even worse, over the next few days the retreating army was beset by horrendous rain storms which turned the roads to mud bogs.

On July 13th, elements of Meade’s Army met up with Lee’s force just as they reached the Potomac, but a difference of opinions forced them to seek counsel from Meade before attacking. Meade was reluctant to do so, but word was also sent directly to Lincoln who ordered Meade to order the attack. But by then it was too late. Lee had pushed his Army across the still swollen Potomac and into safety. Lee destroyed the bridge behind him to keep Buford’s cavalry from following.

The war would drag on for 21 more months.

Union Sixth Cavalry

There is another little known or rarely mentioned aspect to Lee’s escape back to Virginia. Elements of the Union Sixth Cavalry Regiment were moving in on him from the southwest. They had reached Fairfield PA by June Third, just eight miles south. They had attacked one of his wagon trains that were using the Cashtown to Fairfield to Waynesboro road and the Fairfield Gap in the South Mtn, to ferry plundered supplies back to Virginia. Such actions were a severe threat to Lee’s escape and had to be dealt with quickly.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/6th_Cavalry_Regiment#Battle_of_Fairfield

Extremely well done presentation:

This site contains many informative entries:

https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=66719