Part 1: Pickett is all in

In the heat of the early afternoon sun on 3 July 1863, MG Pickett’s division moved out of the shade and protection of the woods on the lower slope of Seminary Ridge. His was the only Confederate division that had yet to see any fighting. He had upwards of 6000 men under arms. About half of them were in BG Armistead’s brigade and the other half about equally distributed between the brigades commanded by BGs Garnett and Kemper.

It is hard to establish just how many men actually participated in the attack on that third day. The two divisions that Lee had designated to support Pickett’s left flank were heavily depleted by earlier battles. Together they probably fielded a maximum of 6000 men.

So, as the massive artillery bombardment subsided, the Union troops watched in awe as perhaps 10-12,000 Rebels emerged from the tree line and began to form a mile-long battle line.

The attack memorialized in history as Pickett’s Charge took place in essentially three phases. Pickett’s division began its march across roughly a mile of undulating but generally open ground aiming at the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. Lee had pointed to a copse [1] of trees as the focal point of the artillery barrage as well as the infantry attack. Each commander had been briefed to converge their forces on that easily visible group of trees – which by co-incidence served as LTG Hancock’s Second Union Corps HQ.

Phase 1 was the left flank’s march to the focal point. The northernmost group of Pender’s division now commanded by BG Trimble replacing the wounded Pender had the shortest march since the two ridges tapered toward each other at their north ends. They came under murderous artillery and musket fire and never actually made it across the Emmittsburg Road. Next to them, BG Pettigrew, replacing the injured MG Heth, had somewhat greater success but only a portion of his division crossed the road.

Phase 2 was Pickett’s march. He started out with Garnett’s Brigade in the lead with Kemper’s to his right and Armistead following. Due to the terrain of Seminary Ridge, he was separated by about a quarter of a mile from the troops to his left. Therefore, his division had to march at a 45 degree angle northward towards the trees. This opened up his entire right flank to intense fire from Union troops to the south on Little Round Top who were not under any direct threat of attack.

Out of the 6000, only a few hundred of Pickett’s men actually reached the top of Cemetery Ridge where they engaged in hand-to-hand combat with Hancock’s defenders. BG Armistead was the only senior officer to reach the wall. He was immediately felled with three (non-mortal) wounds. So ended Phase 3 of the attack.

A small number of Pettigrew’s men also reached the Union line a bit to the north, but were quickly repulsed.

For all of its fame (and infamy), Pickett’s Charge lasted about 20 minutes. That’s all the time it took for the BG Armistead to get his men to the wall at the top of Cemetery Ridge. In that time, 50% of the Rebels were killed, wounded or taken prisoner. Over 300 men per minute were lost — killed, wounded or captured!

[1] See the discussion in other essays of the actual role of this copse as opposed to Zeigler’s Grove.

Seemingly, one of Lee’s major mistakes in planning this attack was that it was so focused on one particular point. The second major blunder was Longstreet’s failure to use Law and McLaw’s divisions in at least a diversionary attack to Pickett’s south.

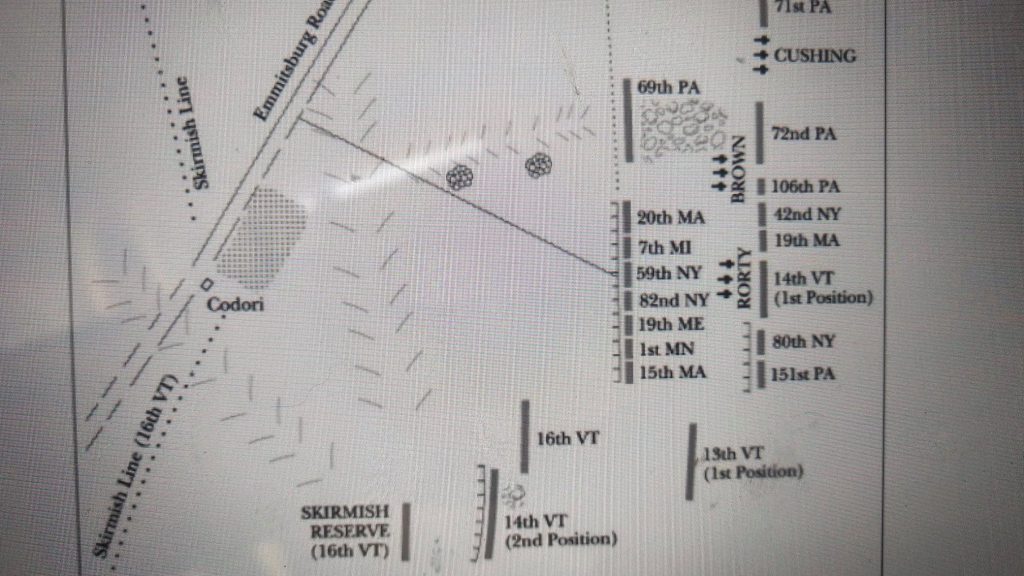

The Union troops to the north and south of that focal point came under no pressure. The 8th Ohio Rgt in the north and 2 Vermont Rgts in the south actually moved forward of and at right angles to their defensive line and aimed devastating enfilade fire into the Rebel lines.

As Longstreet had predicted to Lee, the attack was a disastrous defeat – one of the most severe that Lee had ever experienced.

The Rebels had nothing left to throw at Meade’s Army. They were forced to withdrawal under the cover of darkness and rain. It was a long arduous trek back to Virginia – especially for the thousands of wounded being carried in the wagons that had borne their supplies northward.

====================================================================

Hess surmises that by Day 3 Lee was truly desperate and was in search a miracle result of this last-ditch effort. in only took about 20 minutes for the Union forces to decimate what remained of Lee’s Army!

PART 2: The Union Alignment

Robert E Lee had made certain assumptions about his planned frontal assault on the Union line. He assumed that he could read Meade’s mind and that he had weakened the center of his line by shifting troops to strengthen his flanks. Nothing could have been further from the truth. In actuality, some simple math would have disproven Lee’s assumption. Meade had more than enough troops to man the line. Lee would have had no real way to gauge the Union strength or to know that Meade had the entire 6th Corps in reserve. So Lee’s assumption (delusion?) that the center would be weak was patently false. Meade had a defense in depth near the copse of trees that was the focal point of the attack. Even so, it is generally accepted that the Union force at the focal point of the attach — the copse and the Angle — there were less than 600 men.