Part 1: Running Skirmishes

Day 1 of the Battle of Gettysburg can be made to seem like a ‘minor’ clash of armies. In reality, the number of dead and wounded on both sides rivaled that of the remaining days of the battle.

What started out as a set-piece effort by BG Buford’s 3300 men to delay the advance of Lee’s main body, deteriorated into a series of running skirmishes between units of 200-500 men. Each was a real battle unto itself and produced a number of heroes and zeroes!

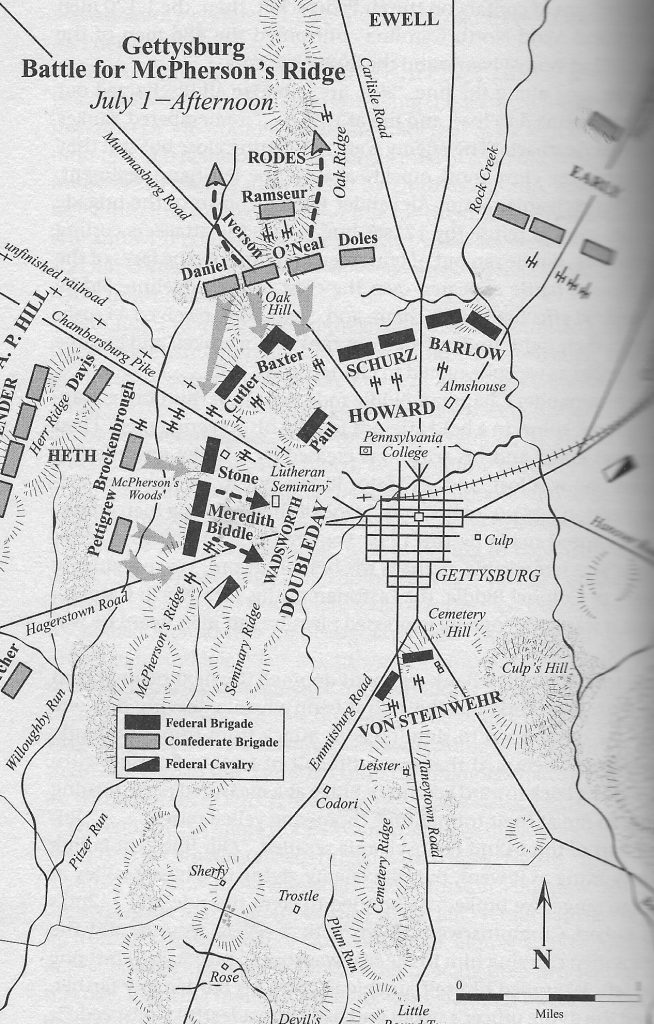

By mid-afternoon, Buford’s men were spent and withdrew from the field. They were replaced by LTG Reynolds’ First Union Corps. By that time Confederate BG Heth had re-organized his scattered division and was assaulting towards the town. Early on, the Union had no organized line of defense; they threw each unit into the fray as it arrived up the Emmittsburg Road.

Their situation was greatly complicated with the arrival of BG Rodes’ division from the north. They were now in a position to out-flank many of the westward facing First Corps units. But a series of errors and failures led to them losing that advantage and many of their men in the process. Instead of launching a ‘surprise’ attack from the north, Rodes chose to bring up artillery to ‘soften’ the Union lines. His delay in attacking gave the new First Corps CDR, Doubleday (following Reynolds’ death), a chance to reinforce and rotate some of his units to face Rodes. When he did finally issue orders to attack, Rodes’ three brigade commanders failed to coordinate their attacks and each was repulsed in turn. One Colonel was reportedly too drunk to command his men; another too far to the rear to respond to the attack order.

Throughout the day, small units clashed and withdrew; repeatedly. Sometimes the same ground changed hands many times, intermingling the dead and wounded.

Other late-arriving elements of Ewell’s Corps moving down from the north skirted the city to the east and might have had a real chance of occupying the high ground south of the city. Early’s failure to push onto those two hills south of the city was perhaps the biggest failure of Day 1.

Buford’s basic plan: to delay Lee’s advance and buy time for Meade to arrive was eminently successful, but at great cost. After Reynolds’ death, it took some time for Doubleday (yes, the baseball man!) to organize his ‘command’. Meanwhile, many of his northernmost units were driven back into the town in a disorganized manner. Many were killed or captured as they wandered the narrow lanes looking for a way south. First Corps had provided no ‘traffic control’ to move them through the city. But this also had the effect of further slowing the Rebel advance to the high ground. By the time they got there, it was firmly in the grasp of First Corps soldiers; many survivors of those small unit clashes on the open fields below. For his part, LTG Hancock had ordered sharpshooters (snipers) to occupy key high-points in the town to protect the withdrawing Union forces.

Part 2:

What started out so well, was a disaster for the Union forces by the end of the day on 1 July 1863. Seemingly, many of the casualties suffered by the Union army could have been avoided if they had been a bit less aggressive in their tactics. BG Buford’s ambush plan was brilliant in both its concept and execution. His 3300 or so cavalry men held off a vastly larger Confederate force for hours until they were exhausted and nearly out of ammunition.

As the Union First Corps relieved the Cavalry, they went on the offensive versus Buford’s plan to fight a defensive action. One of the first Union Brigades to arrive was the infamous Iron Brigade. Instead of simply replacing the Cavalry along McPherson’s Ridge, they charged into Herbst’s Woods in search of the Rebel force to the west. At Willboughby’s Run, they met a larger force of Archer’s Brigade. In a series of violent, regiment-sized unit clashes, the Union forces suffered heavy casualties and one regiment – the 19th Indiana — was nearly wiped out. Had the Iron Brigade simply aligned themselves to the east of the woods on McPherson’s Ridge and awaited the Confederate advance, they likely would have had a much more successful engagement. But one version has them stopping Archer’s Brigade from flanking the newly arriving Union troops, so their charge into the woods may have been more heroic than blunder.

At the north end of the Union line, BG Baxter did essentially that. He aligned his Regiment behind a stone wall and waited for the Rebels. BG Iverson’s Brigade of Rodes’ divison marched south past his unit unaware of their presence. On command, the Union troops rose up and fired enfilade into the Rebel formation. In minutes, Iverson’s Brigade was decimated and had to retreat with about 60% KIA or WIA. Later in the afternoon, however, when Rodes and Heth finally managed to coordinate their two divisions, they successfully drove Baxter and the units beside him from the battlefield. But Iverson’s Brigade – about 1/3 of Rodes’ strength –played only a small supporting role in that final push.

Apparently, one of the most effective Union units was the First Corps Artillery under the command of COL Charles Wainwright. His 21 guns straddled the Chambersburg Pike and supported the Union brigades (including the Iron Brigade) in their defense of Seminary Ridge after they fell back out of Herbst’s Woods. The irony is that they weren’t supposed to be there. As Buford had handled off responsibility for the battle to LTG Reynolds, they agreed that by the end of the day the Union forces should all fall back to the Cemetery south of the city. Late in the afternoon, as the southern flank of the Union line along McPherson’s Ridge began to falter, an order was sent to Wainwright to move his cannons to Cemetery Ridge. A miscommunication ensued. Some accounts blame it on the thick German accent of the messenger. Wainwright stated that he’d never been informed of the plan to withdraw to the Cemetery and he assumed the messenger meant Seminary Ridge. Subsequently, he positioned his 21 guns behind the Union Infantry line. As MG Pender’s Confederate Division mounted McPherson’s Ridge, those guns laid waste to his formation with canister and explosive rounds. This allowed the First Corps infantry to withdraw in a more or less orderly manner back to the Cemetery.

As the Union line broke, thousands of troops flooded into the town: