Part 1:

Over the course of the three day clash of Armies at Gettysburg, nothing whatsoever went the way GEN Robert E. Lee envisioned it.

He had the misfortune to arrive at the battlefront on Day 1 just as Buford’s cavalrymen began their planned withdrawal to their main defense line. He misinterpreted this as a rout and thought that his troops were in command of the battlefield. He immediately departed to confer with LTG Longstreet. In other words, he played no role in that day’s clash. He returned much later in the afternoon, to find that his forces had indeed cleared the field of Union troops, but it had taken them all day to do so. It was then that he got his first look at the formidable terrain that the Union troops had occupied south of the town.

Because of his command philosophy, he was unable to influence the battle and to exploit the gains made on Day 1. Rather than communicating directly to MG Early (who was almost within Lee’s range of vision), Lee sent an order directed at Early through his Corps Commander, LTG Ewell. By the time Early received that order, it was too late in the day to act upon it. Lee wanted him to seize Culp’s Hill; an action that could have changed the entire complexion of the battle but something the Confederate Army never accomplished.

On Day 2, Lee had envisioned a simultaneous attack on the flanks of the Union Army. He saw that the left (southern) flank was the least developed and therefore most vulnerable. He assigned the task of attacking there to his favorite commander: LTG Longstreet. He told LTG Ewell to wait until he heard the sounds of that attack then to launch his Corps at the right flank. Once again, Lee retired to allow his subordinates to execute his plan. It is literally thought that he slept away a good portion on that day.

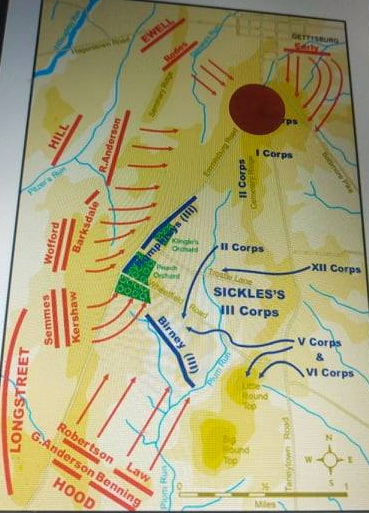

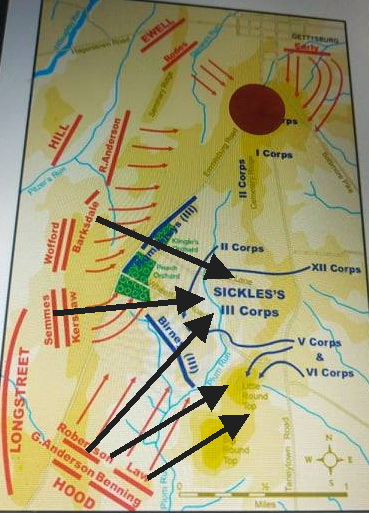

His plan, however, began to unravel almost immediately. Lee gave his orders in the morning but Longstreet took extremely long to organize and move his two divisions into the planned attack position. Part of this was due to Longstreet’s disagreement with Lee’s basic strategy of the attack. Longstreet argued that he should move his Corps farther south and east and attack Meade’s forces as they moved towards Gettysburg. It wasn’t until about 4PM that the Rebels reached their attack position start point. To their surprise and dismay, they found that ground occupied by LTG Sickles 3rd Union Corps. Everything that happened after that was never within Lee’s vision of the attack.

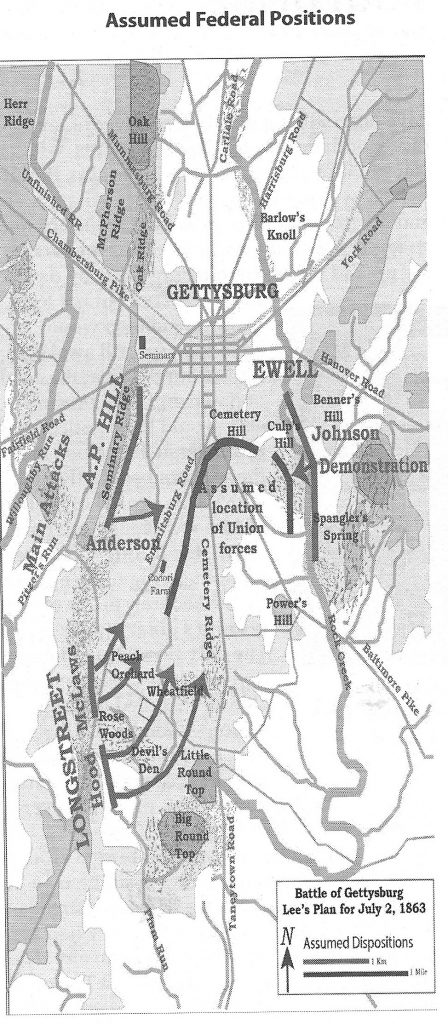

Kunkel provides us with a map of how Lee envisioned the attack proceeding [map 1 above]. Harmon shows what might have happened even with Sickles’ Corps on the way of Longstreet’s advance. In reality, much of Hood’s division got detoured to the east and the resulting engagements at LRT and the Devil’s Den. Likewise, rather than proceeding NE, Law’s troops got caught up in the pursuit of Humphry’s retreat. The black arrows in map 3 indicate the major detours that these forces took, diverting them from the main target at the Cemetery. Meanwhile, albeit belatedly, Anderson and Ewell pressed home the attack towards the Cemetery with varying success.

Because of Longstreet’s late start, Ewell had spent the entire day waiting to move but even when the sounds of battle reached him, he was slow to react and therefore the battle in the north lasted well into the night – a tactic seldom seen in that era.

Day 3 was Lee’s worst. He had laid out a plan whereby nearly three divisions of Confederate troops would assault the center of the Union line. He had convinced himself that Meade – in response to the Day 2 attacks – would have moved troops to strengthen his flanks thereby leaving his center vulnerable. Nothing could have been farther from the truth. What Lee failed to appreciate was that Meade had sufficient troops on hand and that his lines were so compact that he had the entire Sixth Union Corps held in reserve in the rear to allow them to move to any point in his line that was threatened.

The first Day 3 failure was in the preliminary artillery bombardment. Despite the fact that it was the largest use of artillery ever in the Western Hemisphere and something that would not be equaled until World War I, it failed to have any appreciable effect on the Union forces awaiting the attack.

Once again, it was Longstreet’s execution of Lee’s plan that largely led to its demise. Still pouting from the rejection of his strategy from Day 2, Longstreet failed miserably in his role as overall commander of the Day 3 attack force. Of course, the primary attack unit was planned to be Pickett’s Division. His was the only one who had not engaged in any prior fighting and therefore was at 100% strength. Lee had planned that two divisions from LTG Hill’s Corps would support Pickett’s left flank. The remaining two divisions of Longstreet’s Corps would attack on Pickett’s right.

Not only did Longstreet fail coordinate any of the attack plan with Hill, he failed to fully commit his divisions now under the command of Law and McLaws on Pickett’s right. As Pickett’s men stepped forward on the attack. Hill’s depleted divisions also moved (under orders from Lee not Longstreet). But they were stopped by fierce fire from Union cannons and muskets located in the strong point of the Union line in the Cemetery. Their failure to advance past the Emmitsburg Road left Pickett’s left flank completely exposed.

The terrain of Seminary Ridge also played a part in the attack’s failure. A bulge on the eastern slope had left a 400 yard gap between Pickett and the division of Hill’s Corps now commanded by Pettigrew. This gap required Pickett’s men to march at an angle to the left (north) thereby exposing them to enfilade fire. Finally, Longstreet’s failure to fully commit his two (somewhat depleted) divisions on Pickett’s right allowed Union forces to move forward of their main line and continue to attack Pickett’s men enfilade. Lee has envisioned 12-13,000 Rebel troops punching a hole in the Union line. As it was, the portion of Pickett’s division that survived the one mile march from Seminary to Cemetery ridges were the only ones to even reach the Union defenses.

Historians tend to give them great credit for even accomplishing that task. But, in reality, they stood no chance of penetrating that line. Meade’s men, mainly those under the command of LTG Hancock – the most senior Union general on the field that day – were too well prepared for the attack. The preliminary artillery attack had shown them Lee’s plan. Waiting behind the low stone wall that ran the length of Cemetery Ridge were hundreds of Unions soldiers arrayed 4-5 deep. After the fighting on the slopes of the Cemetery Ridge on Day 2, they had policed up the weapons left behind by the dead and wounded of both sides. Those 4-5 men had 8-10 muskets between them. The best shot of the group was in the first rank behind the wall. Those behind were in charge of reloading and passing forward the muskets. Pickett was walking into what could only be compared to the machine gun fire of WW I attacks across no-man’s-land. In addition, Meade had the luxury of moving reserve troops anywhere along his line to defend any gap. When Pickett’s survivors reached what has become known as The Angle for the shift in the direction of the ridge’s stone wall, they were met by a fusillade of fire from those reserve troops.

In hindsight, Lee’s decision to attack the center of Meade’s line was perhaps the worst tactic he ordered in the entire war. By the close of Day 3, Lee’s army was so depleted and he had lost so many of his senior commanders, that he had no choice but to abandon his invasion of the North and retreat back to Virginia. It was only the reluctance of Meade to split his army to pursue Lee that allowed the Rebels to stumble their way back across the Potomac. Despite losing this major clash, the Confederacy would fight on for two more years before Lee’s ultimate surrender.

Part 2:

It is possible to gain some insight into how Lee viewed his role and that of his subordinate commanders by examining his movements of those three critical days. It is generally, agreed that he was absent from the battle site for most of the first two days. IMHO, this contributed greatly to the Confederate loss. On Day 1, it was simply a matter of over confidence that allowed him to return for a scheduled meeting with LTG Longstreet. He had given LTG Hill approval to commit Pender’s Division to assist Heth’s in sweeping the Union Cavalry from the field. Lee saw no other outcome. It would have been in keeping with era military philosophy to hold Anderson’s Division in reserve, but Lee knew that they would not be needed. As such, he could have deployed them to the south. I examine such a movement in Section 28. I firmly believe that this one decisive move could have won the battle and perhaps even the war!

One of the major controversies of the battle developed when Lee returned later in the day to find the Union troops defeated but not vanquished. He was dismayed to find them rallying south of the town on high ground that he himself had not been aware of. His order to Early via Ewell to seize Culp’s Hill “if practicable” will be debated for centuries to come.

Lee’s absence on Day 2 was quite another matter. He had had a long day on 1 July, extending in the early hours of the next day. He was up early and gave LTG Longstreet his orders to attack the Union left flank. But then he disappears until at least late afternoon or even the early evening. History does not record precisely what Lee was doing. I’d speculate that he was sleeping! There is also reasonable evidence to suggest that he was suffering an angina attack that was sapping his strength.

As such, he remained unaware of the delays Longstreet encountered (devised?) in launching his attack. His three Corps commanders were aware of his orders and none would have even entertained a major change. I speculate that Lee had an alternative action: He could have sent Anderson’s Division to attack Sickles-Humphrey’s right flank. The outcome of such an attack was more precarious. Much depended on Meade’s ability to shift forces into that battle space. I explore this clash in Section 25L. I do not see it going in favor of the Rebels, but it would have been a logical alternative to waiting for Longstreet’s 4PM attack to develop.

Perhaps he was rested and at least somewhat recovered from his angina by Day 3. He seemed to be watching every minute of this ignominious defeat. It seems that he had recovered the confidence that he had in his commanders and men on Day 1. He had convinced himself that Meade would have reacted to his flank attacks by reinforcing those flanks at the expense of the center of his line on Cemetery Hill. Nothing could have been farther from the truth. This is where he watched his worst battlefield defeat of the war.