In order to fully understand how this battle was conducted – and perhaps why Lee lost – one must have a full appreciation for how these two mighty armies were organized; how they maneuvered and how they were commanded.

The two forces that were destine to decide the fate of two nations were quite evenly balanced. Both consisted of about 100,000 men. But Meade had perhaps a few more men under arms – as opposed to in the support wagon trains. But that slight difference would not likely have been enough to carry the battle. For this discussion, both armies had nearly 70,000 infantry and well over 120 cannons.

Following the death of Stonewall Jackson, Lee had reorganized his force into three large Corps. These were commanded by LTGs Longstreet, Ewell and Hill. Various historians have assigned numbers to these but I prefer to simply designate them by their commander.

Meade’s force actually was comprised of 15 separate corps, but only 7 were in the Gettysburg area. The primary mission of the Army of the Potomac was to guard WASH DC. That is where the majority of the Army was occupied. Less than half was dedicated to chasing the Rebels across Northern Virginia and now into Pennsylvania.

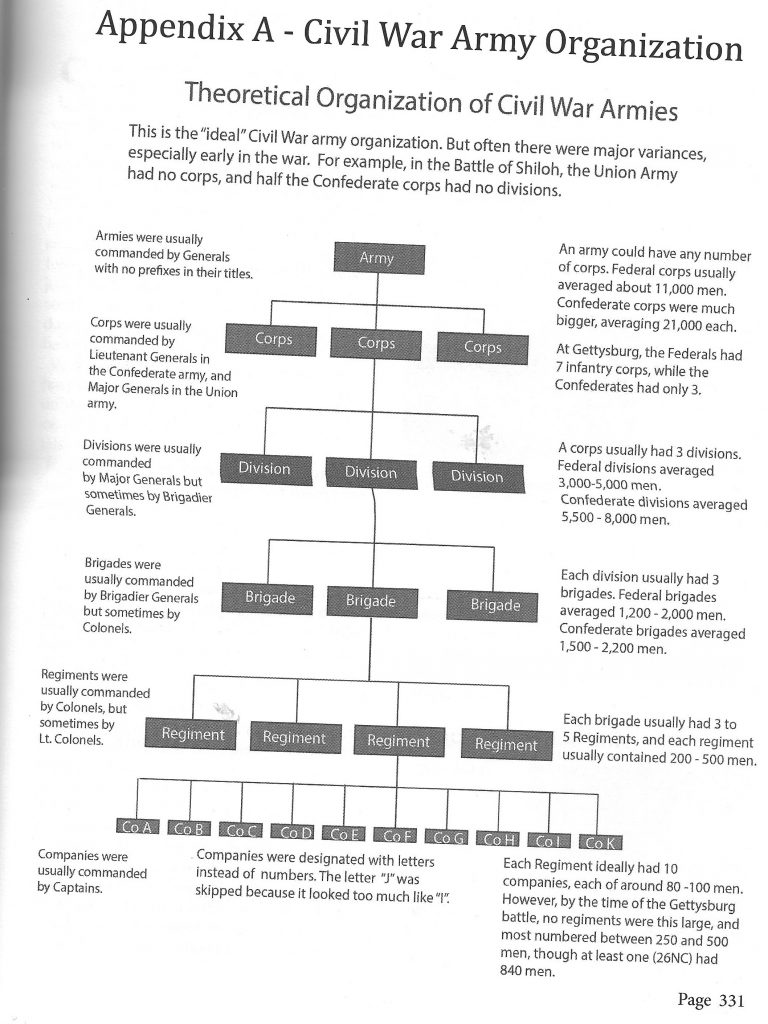

As we move down the Table of Organization, both armies looked very similar. Each Corps had three divisions; each division had three brigades and within brigades there were a varying number of regiments, then companies and platoons. Because of this mirror imaging, at each level of this organization the Union force had significantly fewer fighting men. For the Union, LTG Sedgwick’s Sixth Corps was the largest comprised of 13,000 men, but all the corps ranged from 9-12 thousand. Surprisingly, Sickles’ Third Corps and Slocum’s Twelfth had two only subordinate divisions.

Having been recently reconfigured, Lee’s three Corps were more evenly balanced with 20-22 thousand each; again divided into three subordinate divisions.

The take away lesson is that whenever we talk of two units clashing, a Confederate unit of the same name always had significantly more men that a Union force at the same level. For example, the 15th Alabama Regiment that clashed on Day 2 with LTC Chamberlain’s 20th Maine had over 500 men compared to Chamberlain’s 300. It was at these lowest levels that the numbers varied greatly. This was due to the fact that Regiments were raised at local levels and varied greatly in the number of men available to them. Within a brigade there were usually 3-5 regiments but sometimes up to 7 or 8.

Because it became harder to command when the unit exceeded 2000 men, Confederate divisions usually were divided into 4-5 brigades while Union divisions almost all had only three.

UNION Forces:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Army_of_the_Potomac

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Civil_War_Corps_Badges

CONFEDERATE Forces:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Army_of_Northern_Virginia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ranks_and_insignia_of_the_Confederate_States

Senior Officer Rank:

Among the officers of this era, rank, status and seniority was of particular importance. Yet, at the same time it was a bit less formal than today. In these essays, have adopted a convention to denote the rank of the named officers using the modern-day ranks — perhaps better stated as pay grades. Although the rank did not formally exist, I refer to the most senior members of these Armies as GEN: Lee, Hooker, Meade. A commander of a Corps is tagged as an LTG (Lieutenant General); with MG (Major General) for a Division; BG (Brigadier General) for a Brigade. This is done for clarity and to denote the level of responsibility that these men wielded. It was often the case, however, where the individual was not formally assigned the rank commensurate with his level of command. At Gettysburg, Third Union Corps Commander, Dan Sickles, for example, was a MG not a LTG. Brigades were as often as not commanded by a COL (Colonel) rather than a BG.

The officer corps in both of the armies involved were actually quite small and since West Point, or Annapolis or the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) and The Citadel (The Military College of South Carolina) had produced the vast majority of the senior officers, for the most part they were well acquainted with one another. They all knew who was senior to whom. Whenever and wherever these officers gathered, they were well aware of seniority and its accompanying stature. Hence the friction that developed in the Union HQ at the cemetery on Day 1 when Hancock had to produce a written order signed by Meade to get Howard who was technically senior to him to stand-down and allow him (Hancock) to assume overall command of the battlefield.