As far as understanding the events of 1-4 July 1863, I’d place myself at perhaps a 5/10, with 10 being those with advanced academic degrees in history. But until I read Troy Harmon’s excellent book Lee’s Real Plan at Gettysburg, I didn’t appreciate the factionalism that he describes among the ‘authorities’ on this battle.

In my late-night musings, I came to many of the same conclusions that Harmon describes. I also came to realize that historians tend to place themselves in one of two quite divergent groups when studying an event. One group tends to hone in on the minutest details. Often they will try to follow an individual through the event and see what he sees, feel what he is feeling. They want to account for every minute and count every window in every building he passes. They drown in minutia. Such is the text by Earl Hess.

I belong to the other group. They want to hover above the event – in the past we’d have called this a bird’s eye view; today maybe a drone perspective. They try to avoid drowning in the details and look at a bigger picture. From this overview perspective, one can ask questions of the scene: Why is this unit in this place at this time? How did they get there? Are they supposed to be there? Could they have been better utilized elsewhere on the battlefield?

Prior to reading Harmon, I had not realized that there are two (probably more) factions of Gettysburg experts. They must have some lively discussions when they met up. Some believe that the Round Top-Devil’s Den-20th Maine clashes were a focal-point event of the battle. I tend to have independently arrived at the almost the same conclusion as Harmon and his colleagues: that The Cemetery was Lee’s only focus. For them, MG Hood’s movement to the east was an unintended detour that literally blew-up Lee’s master plan. Of course, LTG Sickles had something to say about that.

This view of Lee’s plan doesn’t necessarily determine that he was correct and that he had a chance in 100 of actually winning the battle, but his almost obsessive focus on the Cemetery does explain a lot about his actions on Days 2 and 3.

A number of times in these essays I have described Lee’s reaction to looking through his field glasses from the Seminary and seeing the cemetery for the first time as akin to thousands of military commanders throughout history who stood outside the walls of a castle and decided that soon that castle would be theirs. Continuing the Medieval analogy, if the series of contiguous hills were the castle walls, the cemetery was the castle keep. Beginning about noon on Day 1, the Union forces had begun to fortify the grounds of the cemetery against an inevitable assault. Their intent was to make it as impregnable as any castle keep could be.

Harmon seems to think that the vision of the cemetery was burned into Lee’s brain and that he was determined to make it his. Harmon goes on to describe all the actions and decisions that he made to capture that tiny piece of the castle. Although it is clear from the way Harmon lays out each of Lee’s actions that he intended to own the cemetery by the end of the battle, I am not quite convinced that he (Lee) was solely focused on that patch of earth. After all, as he got that first glimpse he did not order an assault by Rodes who was the closest force in the immediate area. Instead, Lee focused his attention on Culp’s Hill as the dominating ground above the cemetery and sent orders for MG Early to occupy that hill as a means to deprive the Union the full use of the cemetery. In continuance, he ordered LTG Ewell to have Early and Johnson make attacks on Culp’s Hill on days 2 and 3 in hopes that it would fall.

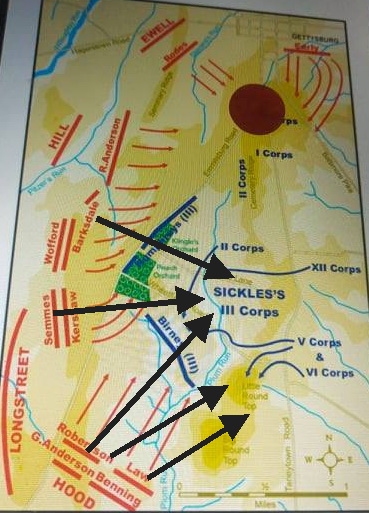

For whatever my opinion is worth, I do whole-heartedly agree that the Day 2 clashes to the east of the Emmittsburg road were driven by events and were a major diversion or detour from Lee’s plan and orders. There never should have been a fight to the death by the 20th Maine! They should have had a rather quiet afternoon in the shade of the woods on the slopes of LRT. Lee never intended nor expected that his troops would be anywhere near that area.

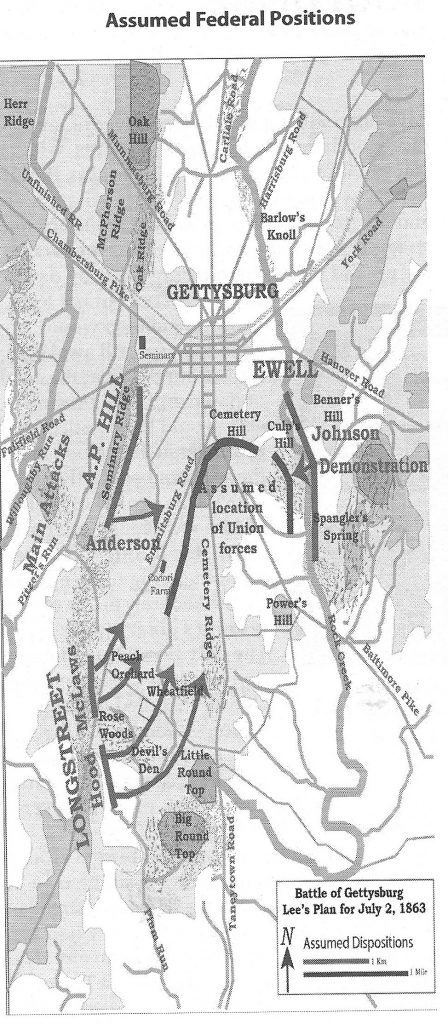

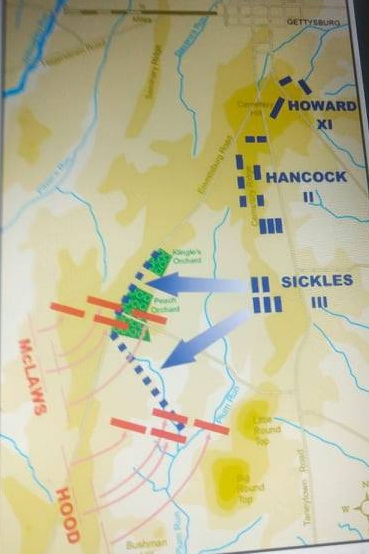

Once again, we look to point a finger at how it happened that some of the bloodiest ground in America is at the Wheatfield and LRT. As seen in this maps from Kunkel’s and Harmon’s books, Lee had ordered Longstreet to swing around the southern tip of Seminary Ridge and assemble in the shadow of the orchard knoll then attack to the north. Instead, at 4PM on Day 2, MG McLaw found that the area he wanted to be in was occupied by MG Humphrey’s division and most of the Third Union Corps’ artillery. It was pure survival instinct that saw MG Hood shift his division to the south and east to get them out of the firing line. From that moment on, Lee’s plan was destroyed and in the heat of battle McLaw’s men abandoned their planned movement north towards the cemetery.

Meanwhile, albeit somewhat delayed by the altered battle taking place to their south, MG Anderson’s Division and those of MG Rodes and Early did their best to attack the cemetery from the west and north respectively. They had but limited success.

Once Lee had made the decision to stay and fight at Gettysburg as opposed to taking Longstreet’s counsel and shifting south, he was permanently committed to trying to take both the castle walls and the castle keep. Unfortunately, his desperation resulted in the ill-fated frontal assault by MG Pickett.