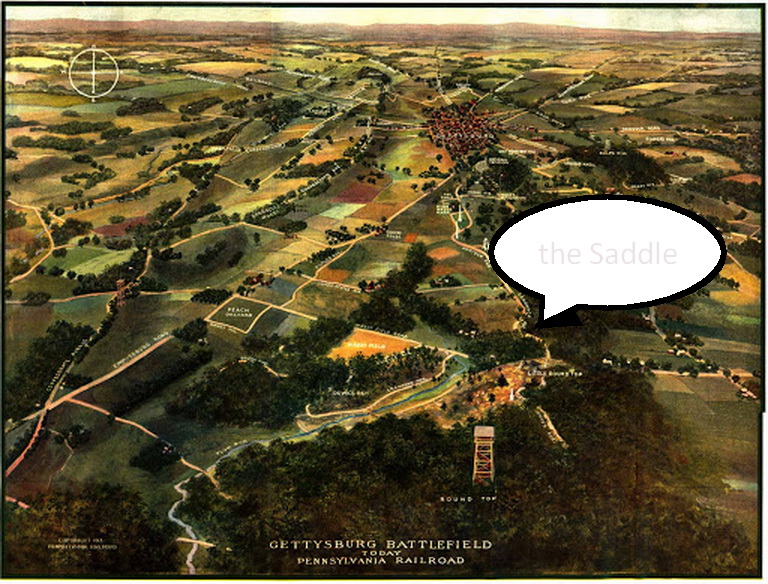

Is it possible for a piece of terrain to be an unsung hero of a battlefield? If so, I propose a candidate. It is a small and otherwise unremarkable stretch of land that I will call The Saddle. It is the low area where the south end of Cemetery Ridge falls away and then the north edge of Little Round Top (LRT) begins to rise.

This section of an otherwise famous battlefield is rarely mentioned when places like Culp’s Hill, the Cemetery, Devil’s Den and the Wheatfield are described as critical points in this most famous of famous battles. The Saddle is simply there, unpretentious and uninvolved. And yet, I present that it was very much involved if only in the most passive way in three aspects of the overall battle and lends itself to one or two ALT Hx speculations. The Saddle will forever be paired with the Peach Orchard as counter-balancing pieces of terrain.

On the morning of Day 2, MG Dan Sickles awoke on a developing battlefield. He was in that Saddle. He didn’t like it! In the mid-afternoon the day before, he had ridden ahead of his corps. As he rode up the Emmittsburg Road he would have passed in the shadow of the knoll which held a large and peaceful peach orchard. We know that he then sought out LTG Hancock who had arrived not long before Sickles and under the direct orders of GEN Meade had assumed overall command of the battlefield. History records his presence with Hancock but nothing of any discussion or exchanges they may have had.

It was on Hancock’s recommendation that Meade ordered his entire command – all seven corps – to converge on Gettysburg. Hancock busied himself throughout the rest of 1 July organizing defensive positions anchored inside the cemetery and spreading out onto the contiguous hills. Like Buford and Reynolds before him, Hancock had determined that the Union position for this battle would be a defensive one. Meade, himself, arrived well after midnight and immediately undertook a rapid ride to assess the position of his forces. Apparently, his first actual order was to have the next arriving unit positioned to extend the Union south from the left flank of Second Corps on Cemetery Ridge. As fate would have it that ‘next unit’ was Sickles’ Third Corps. Since it was only a few hours until dawn and they had had a long march, Sickles had them bed-down on the reverse slope of LRT. In contrast, Twelfth Corps soldiers over on Culp’s Hill worked through the night felling trees to build a solid rampart 2/3 of the way up the hill.

The precise sequence of events of the morning of Day 2 as far as MG Sickles is concerned is also not faithfully documented. He would claim that he went to Meade’s HQ to secure permission to ‘re-align’ his corps for a better defensive position. Others on Meade’s staff remember it differently.

Everything that transpired that morning seemingly harkens back to the Battle of Chancellorsville. In short, Sickles’ Corps had occupied a piece of terrain that GEN Hooker ordered him to withdraw from in order to form a more solid Union line. Just as Sickles’ had predicted, Rebel artillery subsequently occupied that hill and bombarded his corps relentlessly. Sickles was not going to allow a repeat of that debacle. He found himself staring hard at that knoll a few hundred yards to his front, knowing that it was prime terrain for Rebel artillery and a repeat of Chancellorsville. He could not allow that!

During his visit to Meade’s HQ it is even doubtful that he spoke directly with the general himself as opposed to some of Meade’s staff. Whatever the words used, Sickles left with what he interpreted as permission to re-deploy as he saw fit. About noon, he sent a reconnaissance in force consisting of a brigade of BG Humphrey’s division over to the orchard. As they probed to the other side of the Emmittsburg Road, there was a brief encounter with elements of Anderson’s division of AP Hill’s Corps who were just beginning to occupy the western face of Seminary Ridge. Sickles took the report of those troops as proof that the Confederates had their eyes on the orchard. He ordered Humphrey to move his entire division into orchard. Since he only had two divisions in his corps, he had Birney’s division deploy facing south to protect Humphrey’s left flank. This alignment created three significant gaps in the Union line. The largest was between Humphrey’s right flank and the nearest Second Corps unit on Cemetery Hill; a distance of about 2/3 of a mile. There were also small areas on both of Birney’s flanks that were unmanned, undefended. To shore up the gap between the two divisions, Sickles deployed much of his artillery in a line but unguarded by infantry. Almost all of his corps had moved through the Saddle.

Early in the morning, BG Grosvenor Warren, Meade’s Chief Engineer, began a detailed tour of the defenses on orders from Meade himself. He had begun at the right flank on Culp’s Hill and slowly made is way along the Union line which ran some two-plus miles in a U-shape through the cemetery. When he arrived at the far left flank of Second Corps, he found nothing! There were no defenses to inspect, no units deployed, not a man in sight! Stunned would be a kind word for his reaction. He had expected to find infantrymen poised to defend LRT and perhaps beyond. Instead there was only dirt.

Sickles’ entire force was out of Warren’s sight but Sickles himself was barely a few hundred yards to Warren’s west headquartered in a farm house. Warren took two immediate actions. He dispatched a message to Meade concerning the lack of troops and he set off east to try to rectify the situation. Although as an engineer and staff officer and had no direct command authority, he managed to convince COL Strong Vincent to move his brigade on to LRT. Since this unit contained LTC Chamberlain’s 20th Maine Rgt, this bold move likely saved the Union cause later that day. Vincent agreed to move based on Warren’s assessment of the situation, but without orders to do so — a move not unlike Sickles’!

Late in the afternoon of Day 2, the Saddle came into play once again as the remnants of Sickles’ defeated corps withdrew from the battle. They had to pass through there as the easiest route of departure.

There was even a third aspect to this Saddle. It was the seam between two units. Second Corps was to the north and first Sickles’ Third Corps then Sykes’ Fifth Corps was on the south. Anytime an opposing commander can ascertain such a seam, it becomes a prime point of attack. On the north-facing portion of Meade’s line there was a similar seam between Eleventh and Twelfth Corps. It, too, was in the low area between the Cemetery and Culp’s Hill. In one of his probes, Early targeted that area simply because it was a low-lying area. He seemingly never actually identified it as a seam. Unfortunately for him, he was never able to concentrate his troops sufficiently to breach that seam. Upon close examination of the terrain, it might have been obvious that the Saddle was also a seam.

A WHATIF series of possibilities now enters the picture. WHATIF in the late afternoon of Day 2 instead of attacking straight across the valley from Seminary to Cemetery Ridge, Anderson’s men had angled slightly south and attacked into the Saddle? They would have been following Sickle’s retreating men and may have had some success as other Union units might have held fire to allow Sickles’ men to escape. It is impossible to speculate if such a shift of the main attack line might have been successful. It does seem that finding LTR rather inhospitable to placement of artillery, most of the Fifth Corps cannons were in position in the area of the Saddle.

Similarly, one could speculate that– given the tragic outcome of Pickett’s ill-fated attack on Day 3 — it might have been wiser for him to have angled southward to attack into the Saddle rather than attack the heart of Hancock’s Corps at the copse of trees. The seam between Hancock and Sykes would perhaps have been a better choice. Here we’ll have to defer to HARMON’s premise that the cemetery and not a simple penetration of the Union line was Lee’s Day 3 target.

Finally, although once again, the Saddle is not specifically credited as playing a role, the three regiments from Vermont that rotated and extended their line so as to concentrate enfilade fire on Kemper’s Brigade of Pickett’s Division were also in the area of the Saddle and used that undulating terrain to their advantage.

In short, then, I propose that the title of unsung territorial hero be awarded to The Saddle.

In his excellent (and lengthy) book The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command Edwin Coddington sheds some light on the events of the morning of 2 July as far as Sickles’ movements are concerned. It seems that Sickles professed to be ‘unsure’ of where his men were supposed to deploy. Meade seemed to have had a clear idea and whether or not that concept was succinctly communicated to Sickles is unclear. Perhaps Sickles was just being obstinate and wrangling to ‘get his way’’

According to Coddington, Sickles did have a direct exchange with both Meade and his artillery commander BG Hunt. Hunt accompanied Sickles to discuss the placement of Third Corps’ cannons. This discussion involved the Peach Orchard knoll as an excellent artillery platform. So Hunt at least was aware that Sickles was anticipating a shift in his corps’ position away from LRT. Apparently though, due to an artillery attack by Rodes, Hunt did not return directly to Meade’s HQ with any such information. Again, Coddington quotes Sickles’ post-battle report saying that he understood that he had authority to place his troops “in such a manner as, in his judgment, he should deem most suitable.” Others seem to relate a somewhat different level of precision in the orders Meade gave to Sickles with regard to his corps’ placement. However, there is a quote attributed to Meade that does seem to leave room for ‘interpretation’: “any ground within those limits you choose to occupy I leave to you.” It would seem that Sickles’ ‘limits’ were somewhat broader than those actually intended by Meade.

Eventually, Hunt apparently informed someone in Meade’s HQ of his sojourn into the Peach Orchard and this eventually prompted Meade himself to ride off to find Sickles and determine his intentions. At about 1600, they had a face to face confrontation at Sickles’ HQ and Meade was on the verge of ordering him to fall back to LRT, when the opening salvos of Longstreet’s attack were heard. That ended the discussion. For better or worse, the die was cast!

Power’s Hill

https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=249765273155388