In Section 4b I describe the arrival of BG Buford and his cavalry division at Gettysburg and his actions that started the battle. In one sense, he could be considered an Unsung Hero, someone who does not receive the acclaim that he is due. But alternately, he might also be a candidate for Goat in that his action on 30 July went far and above the mission and mandate that he was given to locate Lee’s position. He unilaterally and without orders committed the Army of the Potomac to a battle at a time and a place that no one wanted. I ask you dear reader to make your own assessment as to which title is best pro-offered.

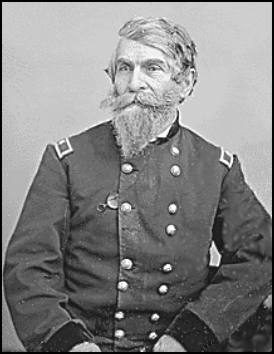

I propose that the true Unsung Hero on Day 2 was BG G. K. Warren. He was the Senior Engineer of the Army of the Potomac. He had arrived on site in the wee hours of the morning of 2 JUL with GEN Meade. They were briefed by LTG Hancock the commander of the Union Second Corps as to the outcome of the first day’s battles and the disposition of Union troops. Meade was satisfied that preparations were well in hand for the next day’s clash and he retired to his HQ in a small farmhouse just on the inner slope of the Cemetery.

LTG Sickles’ Third Union Corps arrived via the Emmittsburg Rd, at the same time as Meade’s command group. He was told to find Hancock’s left flank and to link from there southward. His men had been marching all day and he allowed them to occupy their positions but to settle in for the night without further action. Meanwhile to his north, the Second, First and Eleventh Corps were working through the night to erect and improve defensive positions, breastworks and trenches. As dawn broke the morning of 2 July, Sickles got his first look at the terrain. He did not like what he saw.

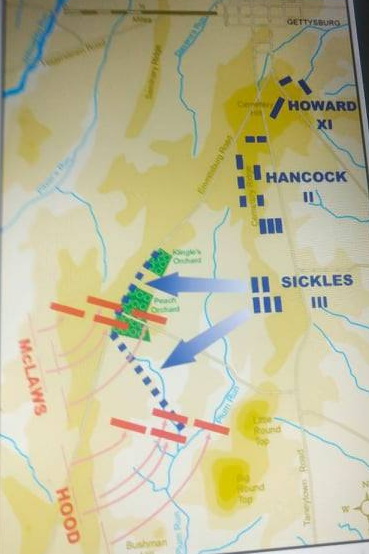

His men were aligned along a long low ridge that we will come to know as Little Round Top. His right flank ran through a saddle, a low area where Cemetery Ridge tapered off and Round Top began to rise. The rocky terrain was not conducive to digging trenches, there were few trees except at the extreme southern end of the ridge that might be used to build breastworks and there was no stone wall as there was along most of the length of Cemetery Ridge to his north. Worse still, from his perspective, there was better terrain in front of him. Of the 7 Corps Commanders under GEN Meade, Sickles was the only one who was not a West Point graduate. He was a lawyer and politician before the war. He did feel confident, however, in assessing that he would be hard-pressed to defend the ground he stood on. Spread out across about a half mile immediately in front of him was a small dense grove of trees known as Rose Woods and just beyond that another larger grove of trees which would prove to be the Peach Orchard, standing on a prominent hill looking down onto the Emmitsburg Road. Sickles made a decisive — many say rash decision — to shift his entire corps forward to occupy that space. He did so without orders and some claim without an attempt to notify GEN Meade – although Sickles would deny that for the rest of his life claiming he sent a message to Meade about his intentions.

Sometime in the late morning, Sickles was on the move. He found, however, that his 10,000 or so men could not adequately occupy the entire front. He sent Birney’s division to the left (south) to anchor themselves on a rocky area known as Devil’s Den and occupy the adjacent woods and wheat field. He led his main force into the Peach Orchard. This left a huge gap in the Union line between him and Hancock’s left flank.

This is where BG G.K. Warren comes on the scene. As Chief Engineer, GEN Meade dispatched him to ride the entire Union line and assess the defenses. He had begun on Culp’s Hill on the right flank and rode through the cemetery and down the adjacent ridge. Overall he was very impressed and pleased with the fortifications he saw. And then, there was nothing! Where he expected to find Third Corps, there was no one. The Union line ended at Hancock’s left flank! He quickly figured out where Sickles had gone and he rode forward to urge him to return to his assigned position, but it was too late. The initial Confederate units had begun to round the southern end of Seminary Ridge and essentially blunder into Sickles’ muskets.

Warren returned to the highest point on Little Round Top and in the bright afternoon sun he could see that Rebel troops were moving east in a grove of trees to Sickles’ south. From that vantage point, he could see that they were on a course that could take them into Devil’s Den and thereby outflanking Sickles’ left flank. Although he is purely a staff officer and has no command authority whatsoever, Warren takes a bold and decisive action. He rode back towards the Baltimore Pike and located a Brigade led by a COL Vincent in MG Barnes’ division of LTG Sykes’ Fifth Corps. Warren ignored these several levels of the command structure and convinced Vincent to move his men immediately to the southern end of Little Round Top overlooking Devils’ Den from which he could support Sickles’ flank which was in jeopardy of being attacked. Vincent reportedly arrived just in time [4th T = Timing] to lend that support and probably to prevent them from being overrun.

Warren then sought out LTG Sykes and had him move into the position that Sickles was supposed to be occupying. It is Vincent, himself, who led LTC Chamberlain’s 20th Maine Regiment into place in the woods at the southern tip of Little Round Top and orders him to “hold at all costs”.

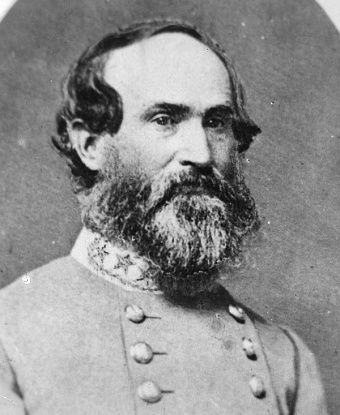

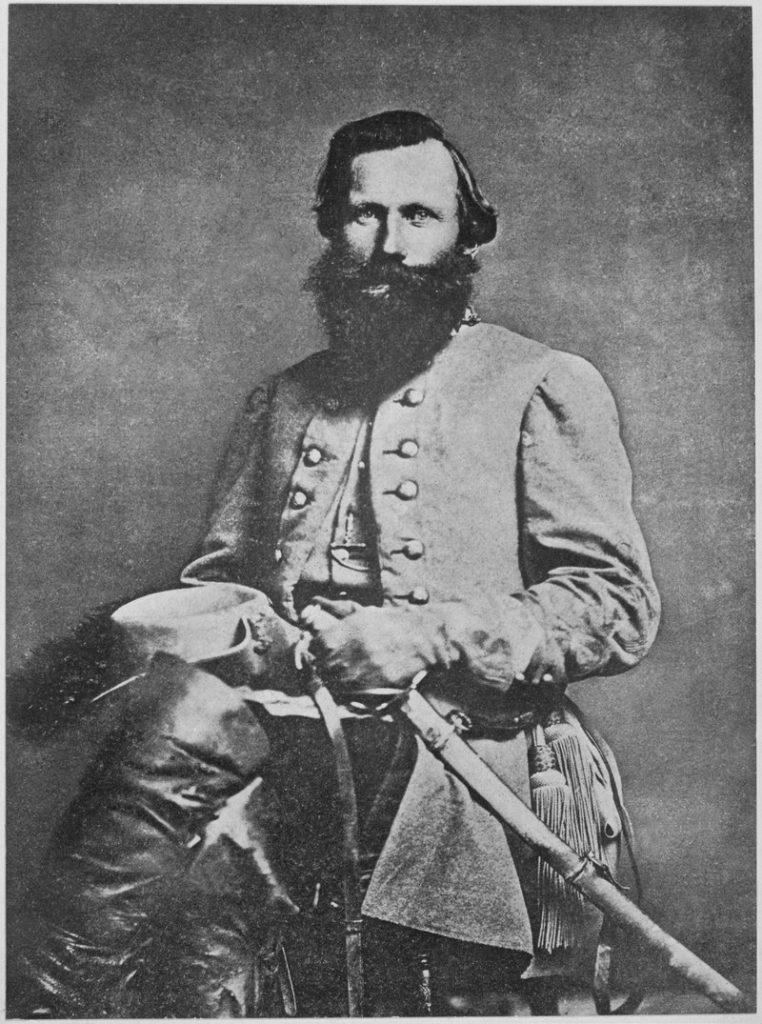

Meanwhile, on the Rebel side, things were also not going particularly smoothly either. Over breakfast, Lee had given LTG Longstreet orders to first find then launch an attack on the Union left (southern) flank. Their expectation was that if Longstreet could break that flank, Rebel soldiers could pour into the inner logistical area behind Meade’s defensive line and cause havoc along the entire front.

Longstreet protested that elements of MG McLaws’ division had not yet arrived on site and that he could not proceeded without them. As it was, his Corps was missing the all-important division belonging to Pickett who had been assigned as the rear guard for the Army of Northern Virginia and was still a day’s march away. Longstreet would be attacking with two divisions against multiple corps of Union troops. He was banking on the element of surprise to somewhat even the odds. BG Law’s brigade consisting of the 14th Alabama Regiment was the last to arrive on the heels of the 4th and 5th Texas Regiments of Hood’s division. It wasn’t until about noon that Longstreet began the 3+ mile march to the southern end of Seminary Ridge. Partway there, he received word that there was a Union Signal unit on Little Round Top and that his planned path would be clearly visible to them. He had to backtrack and lengthen his approach to avoid detection, further delaying the onset of the attack.

When MG McLaws’ division finally swung around end of the ridge in the late afternoon, they intended to form a battle line along the Emmitsburg Road and await MG Hood’s division to form up to their south. This was not to be! McLaws found himself staring into the muskets and cannons of Sickles’ men in the Peach Orchard overlooking the road. The battle began before any of the Rebel units was actually ready to attack. As McLaws’ men returned fire, Hood slipped past his rear and moved into position to McLaws’ east. There they were facing off with Birney’s men in the Wheatfield and Rose Woods. These are the units that Warren had spotted from his vantage point on Little Round Top. As the last units in the long line of march the 2 Texas and the Alabama regiments in a brigade commanded by BG Law found themselves at the base of huge pile of rocks known as Big Round Top. The Texans found a gully and followed it east into the depression between the two hills. The Alabamians climbed up and around the face of Big Round Top. These are the regiments that Chamberlain’s men would engage and eventually drive from the battlefield. At some point mid-battle, MG Hood is severely wounded and BG Law assumes command of the division, but fails to designate a new Brigade Commander further adding to the confusion of the attack.

As the battle raged in front of them, LTG Sykes’ Fifth Corps took up their positions from south to north along Little Round Top eventually linking to Hancock’s left flank thereby sealing and securing the Union line. They were able to provide covering fire that finally allowed Sickles’ battered corps to withdrawal that critical half mile and into the Union rear.

Historians have debated Sickles’ move for a century and a half. Did it save the Union Army from defeat on Day 2? Given the time element, could it have been done better, perhaps drawing upon some of Sykes’ troops to fill the gap between the Peach Orchard and Cemetery Ridge?

Had it not been for the bold and decisive actions of BG G.K. Warren, it is entirely possible that BG Law would be remembered as the Rebel hero who surged up and over the undefended Little Round Top into the rear area of the Union line on the reverse slope and who won the Battle of Gettysburg for GEN Lee.

Unsung Hero #3

Even more than either BG Warren (Unsung Hero #2) or BG Buford (Unsung Hero #1?), the role that BG Geo. S. Greene played in the Union victory at Gettysburg is quite obscure and almost never mentioned when the events of the battle are recounted.

At age 62, G.S. Greene was the eldest general officer in the Meade’s Army of the Potomac. He had graduated from West Point in 1923 – second in his class. He had trained as an engineer and returned to the Academy to teach Engineering. He had resigned from the army in 1836 and began a successful career as a civil engineer. He arrived with his brigade in the early morning of July 2nd and was assigned a place on the east-facing slope of Culp’s Hill as part of LTG Slocum’s XIIth Corps.

Like Buford, he had an innate appreciation for terrain as it pertained to the military situation. He noted that the initial units who had occupied Culp’s Hill (units from the XIth Corps and parts of the Iron Brigade of I Corps ?) had dug trenches on the lower slope of the hill [1]. He deemed these ineffective and vulnerable. He ordered his men to fell trees and construct breastworks higher up on the slope. This they did throughout the morning and afternoon. They were joined by other XIIth Corps units as they arrived.

LTG Sickle’s precarious position at the Wheat Field battle site required immediate reinforcements and GEN Meade ordered LTG Slocum (XIIth Corps CDR) to shift as much of his force as possible south to support Sickles. This left barely 1400 Union soldiers belonging to Greene’s brigade manning those breastworks. Like BG Buford on Day 1, Greene spread his men thinly along the defensive line.

For most of the day all was quiet on this extreme right flank of the Union line. Longstreet’s attack on the left flank had faltered and been repelled. Likewise, the follow-on attack by Hill’s 2 divisions under Pender and Anderson had failed to dislodge the 2nd Corps from Cemetery Ridge. LTG Ewell launched the third offensive from the north and east late in the day.

It was dusk when MG Johnson received Ewell’s order to attack Culp’s Hill. BG Rodes’ attack from the northwest had failed for many of the same reasons Rodes’ efforts the previous day had failed. Precisely as he had done on Day 1, he opened his attack with an artillery barrage. This, however, turned into an artillery duel between his cannons on a hill top just south of the city limits and the Union artillery in the cemetery. After more than an hour, the Union cannons had successfully zeroed in on the Rebels and they were forced to break contact and withdraw. Rodes then sent in his infantry. Under cover of the artillery exchange, a Union Brigade had moved down the north face of Cemetery Hill and taken up positions behind a low stone wall. As Rodes’ men marched east to form a battle line, these Union troops rose up and fired devastating volleys into their midst. Their attack was thwarted even before it began.

Johnson’s was the second of Ewell’s three divisions join in the attack. It was full-on dark by the time he had gotten his men aligned to attack. They quickly routed the men who were left in the trenches on the lower slope of Culp’s Hill and began to cautiously pick their way up the heavily wooded slope. They had no way of knowing that they heavily out-numbered the 1400 Union soldiers manning the barricades above them. Because they were so well protected by these breastworks of felled trees and piled stones, these men easily repulsed the first wave.

By this time, the XIIth Corps units that had been shifted south were returned to their original positions. The Union defenses were becoming stronger and stronger as these men literally “manned the barricades”.

One XIIth Corps unit had a nasty surprise in store. They were marching across the lower slope of the hill, unaware that Johnson was attacking. They were amazed and horrified to see a Rebel brigade passing in front of them as they sought the Union lines above. The Union Cdr deployed his men into a battle line and fired 2-3 volleys enfilade into the Rebels, all but wiping them off the map. They then made a hasty retreat and circled around behind the breastworks before they were mistaken for an attacking Rebel unit.

By the time Johnson’s third wave hit the barricades, they were fully manned by reserves from 1st Corps (6th Wisconsin ?) and that attack, too, failed to advance farther up the slope.

BG Greene’s insightful order to construct breastworks had allowed his depleted force to hold out long enough for the remainder of the Corps to re-assume their positions.

The fighting on Day 2 ended with LTG Ewell sending his third division under BG Early into the fray. Having scouted the area in the afternoon, Early aimed his division at the low area, the saddle between Cemetery and Culp’s Hills. He thought this to be a particularly vulnerable position because it was also the junction between two Union Corps. He hoped that the split command would assist his efforts. His assessment was correct but the outcome was still a failure.

The main reason why armies of this era rarely fought at night was the manner in which command and control was exercised. The course of the battle, the need for reinforcements or the ability to exploit a breakthrough, depended on the senior commanders’ ability to watch the battle unfold. On the ground, soldiers were trained to follow their Regimental flag into the battle. In the darkness of July 2nd, Early and his subordinate commanders had scant ability to follow the battle. No sooner had they had aligned to attack, when the center of Early’s line encountered a mill pond which was too wide and deep for them to wade. They had no choice but to shift east and west to get around it. The subsequent mingling of units further degraded whatever command and control their officers had in the dark.

As soon as their presence was detected, because Rodes’ attack to their right had already been thwarted, the artillery pieces in the cemetery were shifted a few degrees to the east and their bombardment of the forest below began. Added to this, the Union troops, also behind berms all along the slopes, opened fire. Most were firing blindly, but effectively, into the darkness. The small number of Early’s force that actually attempted to scale the slopes were repulsed with heavy losses. Fortunately, Early assessed the futility of the situation and called off his attack. Most of his division had had no chance to even discharge their weapons that evening.

The six hours (1600 – 2200) of intense fighting on Day 2 had resulted in no gains whatsoever on the part of Lee’s Army. Each of his three attacks – south, center and north – had been thwarted with heavy losses. Casualties in the 40-50% range were the rule for the units actively engaged.

BG Buford’s selection of the long line of hills south of Gettysburg as a “good place to win a war” hadn’t quite proven true but the battle was won! Time and time again throughout Day 2, the Rebel forces had threatened to penetrate the Union lines but the combination of the hastily erected breastworks and the ability of Meade to quickly shift units within his perimeter to plug gaps in his lines proved to be the winning tactics and strategy of the day.

[1] Somewhat confusingly, the term ‘lower’ here does not refer to elevation, but rather to geography. Culp’s Hill is actually composed of two sections: the larger upper and a small lower. It is on this smaller hill to the south where these earlier trenches had been placed. Greene was correct in that the Rebels overran this portion of the hill rather easily.

A Goat or THE Goat?

The infamous Battle of Gettysburg was not short on heroes – both acclaimed and forgotten. But there is no question that one of the most questionable commanders on that battlefield was LTG Dan Sickles. He spent the remainder of his life trying to justify his decision to move his entire Third Union Corps forward to occupy the Peach Orchard overlooking the Emmittsburg Road. Had he done so without orders and without informing anyone of his intention?

In order to understand the origins of Sickles’ decision making, it is necessary to turn the clock back days, weeks and even years. To begin with, Sickles was one of only a handful of senior officers in the Union Army who had not attended West Point. He was a politician and a rather smarmy one at that; as a native New Yorker and member of the Tammany Hall group, he was used to running roughshod over the law, the Constitution and his constituents to do things his way. But in point of fact, he and Meade had had no direct animosity between them. It was, at Gettysburg, more the absence of GEN Hooker than the presence of GEN Meade that irked Sickles. Despite being the junior among them, Sickles had formed a bond with GENs Hooker and Butterfield, Hooker’s (and also Meade’s) Chief of Staff. The trio bonded over a love of ‘wine, women and song’. It was said that Hooker’s HQ often resembled a bar / brothel more than a military HQ. It was the kind of place that the highly moral (if not overtly religious) and happily married Meade would have taken great pains to avoid.

But now Hooker was gone and in his place sat Meade who admittedly was still in the midst of trying to get a handle on the dispersion of troops that Hooker had left behind. One of Meade’s first acts was to place LTG Reynolds in command of the 3 Union Corps on the western flank. This was done primarily to simplify Meade’s chain of command that involved 7 Corps in the north and 5 more still south guarding the approaches to WASH, DC.

Meade’s first direct interaction with Sickles was — from Sickles’ perspective — an inauspicious one. Sickles’ Third Corps was included in that western group given to Reynolds, yet on the afternoon and evening of 30 June, Sickles received orders from both Reynolds and Meade that he perceived as conflicting. His response was to ignore both and to send messengers to ask for clarification. If anything, Meade was breaching protocol by addressing Sickles directly without rounting his orders thru Reynolds. To compound this ‘error’, Meade had called MG Humphreys to his HQ as he passed by Taneytown as he closed on Sickles’s HQ. Since Humphreys was subordinate to Sickles and Sickles to Reynolds, Meade had jumped two levels of military command. For Meade, this seemed to be simply a matter of expediency, taking advantage of Humphreys presence as he advanced to close with Sickles. Meade asked Humphreys to pay special attention to terrain as he moved looking for any advantage that the Union could gain over Lee’s Army.

Sickles had naturally been shocked by Hooker’s firing and certainly Meade would not have been his first choice as the new commander. In fact, Sickles probably saw no reason why he wasn’t promoted; he’d show those ‘ring knockers’ how to defeat the enemy!

As 1 July dawned, Sickles waited. He was in a pivotal position about half way between Emmitsburg and Taneytown on the road that linked the two. Pipe’s Creek, Emmittsburg and Gettysburg were all with a day’s march, but he was wracked with indecision. By early afternoon, Meade had been apprised that LTG Reynolds had been killed. LTG Hancock arrived at Taneytown just as the news of Reynolds’ death reached Meade. Meade instructed him to continue on immediately to Gettysburg and to assume command of the battle field. Meade had not yet decided whether or not he would commit his Army at Gettysburg — even though both BG Buford’s and LTG Reynolds’ communiques strongly advised this. Sending Hancock ahead of his troops to assume command, Meade would wait for his assessment before committing the rest of his force there. Knowing that Sickles was within easy reach of Gettysburg, Hancock sent a message telling him to proceed immediately to Gettysburg. Now Sickles had orders from three different ‘commanders to do three different things! Likely unaware of Reynold’s death, Sickles was probably wondering why Hancock was now involved in his movements.

Most accounts of this battle suggest that Sickles’ Third Corps did not arrive on station until the wee hour of the morning of 2 July. But Sickles’ biographer tells a somewhat different story. The last of the Third Corps did indeed not arrive until the morning of 2 July, having been left behind as a rearguard at Emmittsburg, but the bulk of the corps was on station by the late afternoon or early evening of the 1 July. Sickles himself had ridden ahead of his command and was present in the afternoon as well conferring with LTG Hancock.

The bulk of the Third Corps had arrived via the Emmittsburg Road and had therefore passed the Peach Orchard in broad daylight. It seems that Sickles was aware of that prominent terrain feature for nearly 24 hours before he unilaterally decided to occupy it. Seemingly, most orders passed from GEN Meade’s HQ on the morning of 2 July were verbal and no written records survive. Sickles would later claim that he was given unclear orders of where to position his men and had them massed but not positioned on the reverse slope of Little Round Top (LTR).

Post-battle there was also a push-pull controversy over BG Geary’s division belonging to XIIth Corps. Seemingly, since the evening of 1 July, he was isolated at the south end of LRT with a gap of nearly a mile north to the left flank of Hancock’s Second Corps on Cemetery Ridge. Meade would claim that he ordered Sickles to relieve Geary to return north to join XIIth Corps and then Sickles was to fill that gap on Hancock’s left. Sickles would claim that he received no clear orders to do so, but by late morning Geary was in place on Culp’s Hill so some exchange of responsibility seemingly took place. The upshot of all this is that Sickles did not make a spur of the moment decision to shift his two divisions to the Peach Orchard. He had the knowledge of the importance of that terrain for many hours before he moved there.

One of Meade’s staff was his son, CPT George Meade. His post-battle account says that GEN Meade sent him to Sickles’ HQ around 9 AM to “inquire if he [Sickles] had his troops in place”. On his initial visit, he was informed that Sickles was asleep but a staff officer told Meade that Sickles had “doubts” about where he should be deployed. Since CPT Meade had been given no specific instructions as to where to place the corps, he returned to his father for clarification. GEN Meade’s instructions were for Sickles to extend Hancock’s line down to where Geary had been. (It must be remembered that no one at this point in the timeline of the battle had maps or detailed knowledge of the terrain. LRT was in some accounts being referred to as Sugar Loaf Mountain and rarely by any name at all.) By the time CPT Meade returned, Sickles had already departed and seemingly was establishing his new HQ at the Trosle Farm about a quarter mile in advance of Cemetery Ridge. As the rear guard arrived from Emmittsburg, their commander, BG Graham, reported to Sickles at that farm house. Seemingly, at this point in time, about noon, the Third Corps was on the move westward.

Historical records seem to agree that at approximately 11AM Sickles himself arrived at Meade’s HQ supposedly to receive clarification of his positioning. Meade seemed to have a clear view in his mind’s eye as to where Third Corps should be, but whether he could clearly convey that to Sickles or whether Sickles had already made up his mind to leave LRT is unclear. Sickles would later claim that Meade gave him ‘discretion’ as to his precise positioning. It would soon be clear that Meade’s concept of ‘discretion’ were far exceeded by Sickles’ movements. An account by BG Hunt, Meade’s artillery commander, partially supported Sickles’ contention that the terrain immediately west of LRT was “broken and rocky” and provided cover and concealment for any attacking force. Sickles apparently took this as permission to shift his line westward. Sickles was apparently most concerned about the prominence of the Peach Orchard as a dominant artillery position should the Confederates occupy it first.

The most pressing problem created by this shift was that it more than doubled the frontage that Sickles would need to cover compared to simply extending a straight line south from Cemetery Ridge. In addition, Sickles line was now bent with Birney’s division facing south in the area that would become known as the wheatfield and Humphrey’s facing west on the Peach Orchard hill. Third Corps was one of two in Meade’s Army that was composed of only two divisions, but even with a full complement of three divisions, it is doubtful that Sickles could have adequately defended his new position. Neither Sickles nor Hunt seemed to be overly concerned that there was now a 1000 yard gap between Humphrey’s division in the orchard and Second Corps left flank on Cemetery Ridge. To bridge the gap where his line turned south and eastward, Sickles inserted his two dozen cannons, but since he had insufficient infantry he deployed none to protect them. It was these artillery pieces that would initiate the battle as McLaws’ division rounded the southern end of Seminary Ridge en route to locating and attacking the Union left flank.

Lee’s instructions to Longstreet that morning was to form up his two divisions (McLaws and Hood) at the southern end of Seminary Ridge and to move north along the Emmittsburg Road to contact with the Union flank which Lee believed would be overlooking and protecting that road. It is questionable that any of the Rebel commanders had any knowledge of the Peach Orchard as a desired terrain feature.

Seemingly Sickles had been eyeing – with concern – the Orchard for a few hours; since before his 11AM visit to Meade. Reportedly, there had been reconnaissance by both sides in that area since early morning and pickets had been exchanging fire often. As these exchanges escalated throughout the morning, Sickles became convinced that this was the vanguard of a Rebel attack from the south. He was wrong, it was actually Wilcox’s brigade of Anderson’s division of Hill’s Corps that was conducting a recon-in-force and was unrelated to Longstreet’s movement to contact. Immediately after receiving notice that Humphrey’s division was in place, Sickles ordered Birney to move forward and south to the area of the wheat field. According to Humphreys, he notified BG Caldwell of Second Corps, immediately to his right that he was moving, but word of his departure went no farther. And so the lines were set for the Day 2 encounter.

Did Sickles truly act solely on his own? Was he the only one concerned about the dominant position that the Peach Orchard could provide? Not according to what Sickles told Humphreys: Sickles said that a division from Second Corps and another from Fifth Corps were prepared to support his initiative. Sickles (rightly or wrongly) seemed to believe that he had the full support of adjacent units in making his move.

It should be noted that Fifth Corps had been held in the rear as the reserve force until the late morning arrival of Sixth Corps who took up the reserve role and Fifth Corps was shifting forward to occupy the south end of LRT as Sickles was creating the gap in the Union line. It was COL Vincent Strong’s Brigade of Fifth Corps that included the 20th Maine Regiment under LTC Joshua Chamberlain that arrived first on LRT.

Accounts of the “spectacle” of Sickles’ movement by Second Corps officers seem to contradict that they had any understanding of what he was doing or that they were to play any role in supporting his movement. Seemingly, neither COL Strong nor any other Fifth Corps officer was aware of what Third Corps was doing, much less being prepared to support it.

All told, Third Corps had far too few men to adequately cover the huge front that Sickles wished to occupy and protect against what he saw as a pending Rebel attack. Brigades were separated by large gaps, some covered by artillery others not.

As the zero-hour of 4PM approached, Sickles had throughout the morning and afternoon made a serious of blunders. In series, Sickles had misinterpreted (or simply ignored) Meade’s orders, had misinterpreted the battlefield reports of heavy skirmishing as an impending attack and had somewhat over estimated the importance of the Peach Orchard and the Emmittsburg Road it overlooked. But the sum of these ‘errors’ had somehow resulted in his Corps being directly in the path of Lee’s planned attack.

In post-battle accounts, Lee makes mention of “a steep ridge” as a desireable position from which artillery could be brought to bear on the Union line on Cemetery Hill. He never named this ridge. Was it the Peach Orchard or simply a portion of Seminary Ridge? There is one line in one report that states that by the end of the day, Longstreet had occupied this sought after advantageous ground. The only promotory that fits that description is the Peach Orchard.

Perhaps the only thing that all the recorded accounts of that Thursday afternoon agree on is that both parties were surprised at the sudden appearance of large enemy units in their area. Longstreet fully expected to be able to push his two divisions around the south end of Seminary Ridge, to re-align into an attack formation and move to contact guiding on the Emmitsburg Road. Humphrey in the orchard was focused on the lower slopes of Seminary Ridge in front of him rather than the road coming up from the south. Birneys was still positioning his division in and around the wheat field as McLaws division came into view.

Most superficial accounts of Gettysburg’s second day gloss over the precise timing of Sickles’ move forward. Again, John Hessler (Sickles’ primary biographer) provides the data: MG Birney arrived in position in strength around 3:30. McLaws rounded Seminary Ridge about 4PM! Hessler writes that “Sickles move forward, for better or worse, forced the Confederates to modify their plans. Sickles advance, more than any individual action, dictated the flow of fighting on Gettysburg’s second day.”

I’ll cease this essay here. I’ve attempted to summarize the events that led up to the clash of forces on the Union left flank on Thursday, July 2 1863. It is not necessary to continue to describe the chaotic series of engagements that comprised that battle. Suffice it to say that by the end of the day Confederate forces held the Peach Orchard but both sides were so depleted that this “dominant” position never played a significant role in the subsequent battle.

Prescient or Impetuous?

One aspect of Sickles move has always puzzled me. Why did he position Birney’s Division where he did: facing south? His primary objective was to occupy the high ground of the Peach Orchard. He accomplished this with Humphrey’s Division. Birney’s main job was to protect Humphrey’s flank. But why his left flank and not his right? Ideally, with a standard three division corps, the formation would have looked like a ‘U’ with a division on either side of Humphrey, But that was not to be.

Let’s examine the military situation as Sickles knew it to be just prior to his movement. The entire battle on the previous day had been to the north. Sickles scouts had reported encountering elements of Anderson’s Division on the east-facing slope of Seminary Ridge; immediately to the north of the orchard. It would not have been difficult to hide an entire division in those woods. Every threat that was known to exist was to the north. Yet, Sickles placed Birney facing south. He essentially left Humphrey’s right flank completely exposed to an attack from the north. So what threat was he protecting Humphrey against from the south? Could he have seen a developing military situation in that direction? Was he truly expecting Rebel troops to march around the southern end of Seminary Ridge? Of course, that is precisely what Lee had ordered Longstreet to do. But how and why would Sickles have anticipated this? I use the word prescient to ask whether Sickles was smarter than anyone gives him credit for. Did he, in fact, anticipate Lee’s flank attack as opposed to an attack launched by Anderson from the north? This is precisely the area that Pickett would emerge from on the following day. [in Section 25k, I postulate how Lee might have altered his Day 2 plan in light of the delays encountered by Longstreet and sent Anderson to attack in his place.]

A simple look at a map of the day shows how Sickles was ‘closing ranks’ as it were to his left, but with no real threat in sight at the time. Why would he have completely ignored the threat that Anderson might have posed and guarded against a completely unknown threat on the opposite side of his formation. Remember, too. that in placing Birney so, he had left a gap of nearly three-quarters of a mile behind Humphrey’s right flank. Why did this make sense on 2 July 1863?

The Rebel ‘Goat’ of Gettysburg

I have nominated candidates as Unsung Heroes – all on the Union side. I have also placed LTG Sickles’ name in nomination for the Union Goat of Gettysburg. This musing involves how MG Early might be the Confederate Goat of the week – perhaps three times over.

It all cycles back to the revelation that GEN Lee had when he climbed into the cupola of the seminary in the late afternoon of 1 July and got his first view of the tactical position that the Union army was occupying. His astute military mind immediately grasped the seriousness of his plight. I have come to likening it to Lee being like hundreds (thousands?) of commanders before him throughout history as they gazed upon the looming castle walls and pondered how they would breech those walls to attain victory. As Lee looked off into the distance, he thought that he perhaps saw an open back door to that Union castle. If he could occupy Culp’s Hill he could disrupt the entire Union line. He fired off a brief message – and it did seem like a message more so than an order – that MG Early should move to occupy that hill “if practicable” [sic]. Unfortunately, Lee’s command philosophy prohibited him from communicating directly with Early. Lee’s message had to be sent to LTG Ewell for him to convey on to Early. Therefore that messenger had to ride far to the north to deliver the message to Ewell then turn south and east to hand it to Early.

Early would claim in his late night meeting with Lee, Ewell and Rodes that he received that message much too late in the day to initiate any kind of military action. Early was supported by Ewell when he presented a series of arguments against moving to try to occupy that terrain. He pointed out that the orders he received to return to Gettysburg included the admonition not to engage the enemy in any significant action until the Army of Northern Virginia was consolidated. He had back-tracked his men about six hours before engaging in a brief but intense battle in which he broke the Union right flank. He then proceeded (without orders) to move his division down the east side of the city and establish a camp to allow them to rest and eat. In the intervening time, before he received Lee’s message, his scouts had (erroneously) reported Federal troops approaching from the east, so he re-positioned a full brigade to thwart any such movement on his flank. He further contended that he received the message too late in the day to react with any troop movements; he did however send scouts to determine the status of the terrain and they found no Union troops there. [Seemingly by approaching from the north and west they had completely missed the elements of the Iron Brigade that had been sent to attain a foothold and were digging trenches on the lower east side of the hill.]

So from Lee’s perspective, Early was (1) out of position and disconnected from the rest of the army; (2) he had failed to occupy the hill and now (3) he required the commitment of MG Johnson’s entire division to bolster attempts to attack the hill on Day 2 — and again on Day 3 when that attack a failed.

Lee wanted to be furious with Early for his placement of his troops and failure to act, but he was enough of a leader to recognize that Early had acted in the best interests of his men if not the overall objective of the army on that afternoon. An additional argument could be made that his arrival from the east due to Lee’s orders to separate him from Ewell’s other two divisions denied him of any direct knowledge of what was transpiring with Hill’s Corps on the west side of town. So Lee could not truthfully even make an argument against his acting unilaterally to move down the east side of the city.

All of the above, however, had thwarted Lee’s intention to fully consolidate his army. On the morning of 2 July 1863, Lee’s army looked like this:

2 divisions (Early & Johnson) were detached on the east side of the city;

Heth’s division was battered and beaten down if not overtly defeated;

Pender’s division was in better shape but Pender was wounded and the untested Pettigrew was now in command;

Anderson was unbloodied but still not in a tactically important position;

Rodes was perhaps the best placed division at the SW corner of the city staring up into the cemetery;

None of Longstreet’s corps was yet fully in place.

Lee’s ‘consolidation’ was looking rather chaotic.

CSA Goat #2

My second candidate for CSA Goat is MG J.E.B. Stuart. I have described his failings in Section 23a and will offer that essay as evidence that he — perhaps more than any other — contributed to the tragic Confederate loss ay Gettysburg.

If there was an Unsung Hero within the Confederate camp, I’m not sure I see him clearly. Lee nor any of his senior commanders seemed to live up to the reputation that they had built for themselves over the past two years of war. None of them stand out as making a major contribution to snatching victory from this awful defeat.

Shared blame?

Perhaps it was simply a symptom of Lee’s angina that he was not operating at top capacity that week. When he made the rather bold move to split his force and send Early eastward “un- accompanied” as it were, he seemingly opened the door for his eventual defeat. Early’s role was to disrupt Union reinforcements from reaching Harrisburg. But it is not clear why Lee thought that Ewell would need two full divisions to attack Harrisburg. After all, it was defended by only a few poorly trained and equipped local militia.

What no one seemed to be concerned about was what might develop behind Early; in his rear as it were. IMHO, Lee should have placed one of Ewell’s divisions at Gettysburg as a rear guard for the other two. This simple move would have all but precluded Buford’s ability to organize the 1 July ambush. At the very least, Early would not necessarily have needed his entire division to rip up tracks at York. Even one brigade left to ‘hold’ Gettysburg may have been sufficient.

Why no one seemed to raise this question with Lee forces me to say they all shared the blame for what ensued.