[see the earlier parts of Section 28 to see the ALT Hx scenario that these two great armies were faced with]

PART 1: the impact

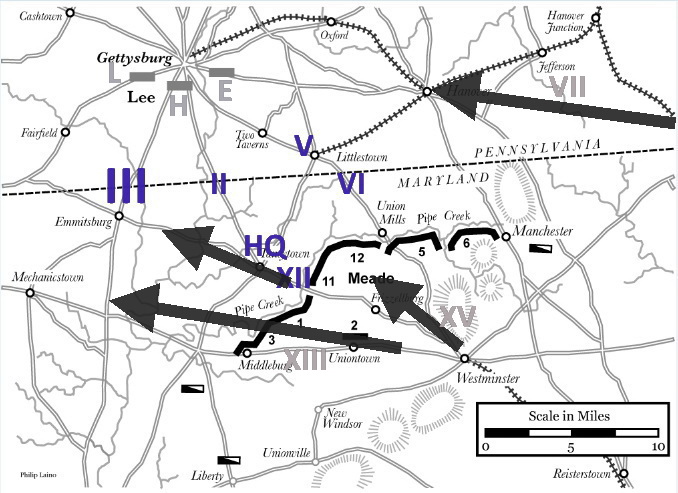

The full impact of the loss of 1st and 11th Corps and a host of senior staff officers had hardly set in when GEN Meade fired off telegrams to President Lincoln to get permission to shift forces north from the BALTO-WASHDC defensive lines. Using the excellent rail connections two replacement corps could arrive at Westminster in a matter of hours.

But Meade had more in mind. 13th Corps would be sent to back-up Sickles at Emmittsburg. His 2-division corps was dangerously exposed on the left flank. The next available corps would be held in reserve at Pipe Creek. But Meade had taken a lesson from MG Early’s advance on York seemingly as an effort to sever the rail connection to Harrisburg from the south. Meade wanted to send one additional corps to Hanover MD. From there, he could threaten Ewell’s two divisions on the Confederate left flank.

He also fired off orders to Harrisburg and Philadelphia for them to dispatch all available militia towards Hanover as well. They would act as support and logistics for the infantry. He also had the bulk of his cavalry stationed to the SE of Gettysburg who could also be used as combat support.

He felt that he had is army reasonably well positioned, if a bit stretched out, blocking the three main avenues south out of Gettysburg across a 10-12 mile front. 5th and 6th Corps were on the BALTO Pike. 2nd Corps was just outside Gettysburg on the Taneytown Road with 12th behind them at Taneytown. He worried a bit about 3rd Corps alone at Emmittsburg but the 12th could move quickly if it looked to be a threat there before the 13th arrived. All those corps commanders understood their assigned positions should he order a fall-back to Pipe Creek.

It wasn’t long after breakfast on 2 July that a very nervous LTG Sickles arrived at Meade’s HQ near Taneytown. He had just figured out that his two divisions were all that stood between LTG Longstreet’s Corps and Westminster. He was sure that he would imminently be attacked from the north and west. What was Meade going to do to protect him? Meade’s promise of the arrival of the 13th and that 2nd was watching over him from his right flank, quelled his anxiety somewhat, but not completely. For the moment he was still isolated on the flank. Meade then directed his artillery commander, BG Hunt, to shift as much of the artillery reserve as he deemed fit in the direction of Emmittsburg as a further assistance.

Truthfully, Meade was just a little more concerned about Emmittsburg than he let on. He knew that Longstreet was Lee’s most experienced and trusted commander. Lee also favored flank attacks as his go-to tactic. Even if Lee did not yet appreciate how vulnerable that city was with only Sickles small force there, he might still decide to launch Longstreet on a march aimed at Westminster via Emmittsburg. Soon after Sickles departed, Meade second-guessed himself and ordered 12th Corps to move west to a position between Emmittsburg and Taneytown. They’d be in position by night fall.

With his cavalry and picket lines stretched out in a long (about 15 mile) arc, Meade was convinced that he could detect any attack threat that Lee offered and react accordingly. Meanwhile, he tasked his Rail Operations staff to begin to shift supplies to York and Hanover to prepare for a counter-attack. It would take him until at least late on the 4th to get troops and supplies to Hanover. He was hoping that Lee would be content to rest his troops at Gettysburg for a few days while planning his next move. Both armies had had a long march north and both could use a few days to recover. GEN Hooker had decided to leave most of his wagons and bulk supplies in Westminster and Hagerstown. This allowed the infantry to move faster, but now they needed food and supplies. Lee obviously had to keep his logistical trains close by which slowed his progress. It would be quite likely that when he moved to attack, he’d leave much of that at Gettysburg and Cashtown.

Meade’s new plan was to stage an attack on those wagons by sending the vanguard of infantry from Hanover. Simultaneously, he’d sweep his cavalry to the east and into the city as support and stage lightening raids on the assembled wagonmasters. Ideally, he’d bring up siege mortars on railcars to act as artillery support, but he doubted that he had time to do so. With all of his chess pieces in place or en route, he was content to wait. As an island of the Confederacy in Pennsylvania, Lee was under more pressure to keep his army moving.

Barely 12 miles of mainly open farm land separated the two armies. There was not much in that space that Lee could use. Nor did Gettysburg offer much of use except general use items. Unfortunately, Meade knew that Ewell had managed to plunder at least some military supplies from Carlisle before he was recalled to Gettysburg. None the less, Meade had his scavenger parties further depleting the terrain to his north to siphon off anything that might be useful to the Rebels.

It was still a lingering fact that neither commander had a clear picture of what he faced. Scouts and spies in the Cumberland Valley that Lee’s army had traversed, were reporting that he had his entire force of perhaps 100,000 men with him and that the last of the infantry (Pickett’s Division) had exited the valley at the north end of South Mtn on or about July 1st. Camp Carlisle reported that Ewell left there the night of the 30th. So Lee’s entire force was indeed consolidated at Gettysburg. How long before they marched south?

Lee was struggling with those same questions. Where was Meade’s force and how could he best attack them? Late on the afternoon of July 2nd, MG Stuart finally arrived with his cavalry division. Lee would need to insert them with Hill’s Corps to replace the losses of the battle so far. Heth’s Division was no longer a combat-capable force. The wounded Heth was replaced by BG Trimble. Their duty now was to guard the tens of thousands of prisoners. He had to get them separated from his army. One, they were a burden to feed. Two, they might become a threat to his rear area as he moved away. He had to begin to shift them west and north away from the immediate area.

Pondering the available maps, he could see that Emmittsburg was the closest city. He also had determined that that is where the two Union corps now removed from the battle had started from. How large a force could Meade possibly have on that flank? Should that be his first objective? But surely Meade would be reinforcing his left flank so it might not exactly be undefended. He’d have to probe in that direction first.

The two other roads that went south also presented interesting possibilities. The BALTO PIKE was the better road, wide and developed for fast movement of both infantry and artillery. But surely Meade would have the area around Littlestown heavily defended and from there it was a longer trek to Westminster. What little Lee could remember about the rail system told him that Westminster was the likely to be Meade’s logistical hub. The third road, through Taneytown, was the most direct route there.

East to west, Littlestown to Emmittsburg was about a 12 mile distance. However many troops Hooker/Meade had brought north to chase him had to now be spread across that distance to block him. He certainly had the concentration of forces as his advantage. But which route south towards Baltimore and Washington should he choose? His original plan of a far northern swing through Harrisburg towards Philadelphia was now dead. He had no choice but to direct his efforts south. Meade would have to drain more forces from Baltimore to replace the corps that he lost. How many troops would Lincoln allow him to pull away to the north? After all, with him in PENN, there was no immediate threat to WASHDC from the south. Should he move quickly before Meade had an opportunity to move too many troops north or should he sit tight and devise a well thought out plan? Longstreet would undoubtedly advise the former; he was leaning to the latter. Bolstered by the success of 1 July, he’d use the next few days to drain away the prisoners; rest and resupply his men and devise a fool-proof plan of attack. But first, he needed to re-align his three corps. To his mind, Hill and Ewell had to exchange places. Ewell would need to move to the center and aim at Taneytown. Hill would move over to the BALTO PIKE and would be augmented by Stuart. The Pike was the longest of the three approaches to the south and would be best suited to fast moving cavalry supported by Hill’s two remaining divisions. Not a great distance to cover, but still a chore to shift 50,000 men. Meanwhile, the streets of the city and the earlier battlefield to the west were teeming with supply wagons. Captured Union wagons and those dragged in by Stuart would provide transport for the prisoners who could not be herded west on foot. Union officers would be separated out and sent to Carlisle where they would be paroled with an oath not to rejoin the fight; standard practice of the era if not always lived up to by the parolee! At least he wouldn’t have to feed them!

As the sun set on July 2nd, Lee assembled his senior staff for a war council to decide the next chess moves. Meade was content to await Lee’s next move as he shifted his new chess pieces onto the game board. Lee had all he was ever going to have; Meade had options.

Part 2: To go or not to go?

Lee’s evening war council was rather contentious. Longstreet wanted to move fast and hard. Ewell was more cautious. Hill stood somewhere in the middle. He was still dealing with the news that he now had to deal with Stuart as a subordinate who likely would see that as a demotion. The overall outcome was that each of the corps would set out on the morning of the 3rd to probe south along their assigned routes. Lee’s two standing orders were re-issued: 1) don’t get too far afield from the rest of the army; 2) do not become heavily engaged before stopping to assess the consequences and alert him to any contact.

For the advance forces, this would be a movement to contact; an effort to determine the position and strength of Meade’s forward line of defense. They were to move cautiously but rapidly; always ready to pull back when the enemy was encountered. No attack was included in this probing action; just location.

Given the consideration that Emmittsburg might still likely be the most vulnerable of sites, Longstreet would split his corps with Pickett moving towards Fairfield while McLaws and Hood marched directly. Assuming they’d encountered the Union line first, Pickett could then attack from the west.

At day break on 3 July, Stuart would launch his cavalry down the Pike, with Hill’s infantry following in support. Hill wasn’t sure if it was a blessing or a curse to have Stuart surging off ahead of him. Pettigrew, replacing the wounded Pender, marched off first with Anderson in trail. Trimble had replaced the wounded Heth and was humiliated by his role of prisoner warden.

Ewell was aware that the 2nd Union Corps was poised not far down the road somewhere between him and Taneytown. His might be the first scouts to locate an enemy force. Johnson would take the lead followed by Early and then Rodes.

Within minutes, a series of cavalry scout messengers were arriving at Meade’s HQ with notice of movement on three fronts. Meade had anticipated such a move and had instructed all concerned to make a slow, quiet withdrawal when approaching troops were sighted. Short some trigger-happy private, he hoped to draw Lee’s men further afield, deeper into territory he controlled.

But Lee never intended a major attack to the south. Many men never actually left the immediate area of Gettysburg. Only advance regiments moved off to probe for the Union pickets. Lee never really wanted to extend his main force more than a few miles away from the city. He was only mildly concerned that Meade might actually be so bold as to launch an attack to the north, but he wanted to protect his assets as it were. Hence, Lee did not want to be drawn into an ambush situation.

As one might have guessed, it was Stuart who drew first blood. As he rumbled down the Pike leaving the infantry far behind, he stumbled on to a squadron of Union cavalry who were crossing the Pike as they shifted easy towards Hanover. Stuart’s men quickly ran them down. Fortunately for Meade, the Lieutenant in charge did not know the whole plan as to where he was headed except to join more cavalry so their capture was no major threat to Meade’s Hanover attack plan. Stuart held his men at Two Tavern’s to give Hill time to catch up.

As if he were in an unspoken race for bravado, Pickett set off smartly down the Fairfield Road. When he and his advancemen rode into town they found the residents cowering in their shuttered homes. Other Confederate cavalry had passed through a few days before as they were screening the main Rebel force heading north. The town’s people were expecting more. Pickett and his command group holed-up in a tavern and awaited orders from Longstreet. He sent scouts towards Emmittsburg.

Johnson’s Division leading Ewell’s Corps marched back into Maryland along the Taneytown Road without ever encountering Union soldiers. The Union 2nd Corps was supposed to have been waiting for them but none were in sight. But just about every barn and hill along that road was occupied by a sharpshooter (sniper) and observers. They intended to remain hidden until they spotted a cluster of officers that would indicate the presence of a senior commander.

Frustrated that none of his scouts were reporting any contact, MG Johnson gathered his staff and trotted to the front of his formation. He chose a bluff that gave him a long view down to the south and was scanning the horizon when the shot rang out. He was off his horse before anyone actually heard the report. The Minie ball had shattered his field glasses before coming out the rear of his skull. His stunned staff halted the advance and sent word to LTG Ewell.

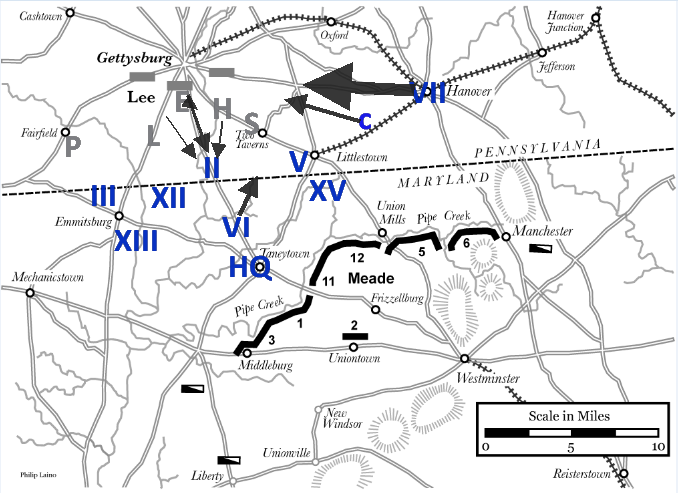

A generally cautious commander, Meade acted almost immediately to word that one of his sharpshooters was certain that he had killed a division commander – exactly who was uncertain. But the Rebel column had halted just south of the Mason-Dixon Line. He ordered MG Hayes, who had replaced Hancock as the 2nd Corps Commander, to assess the terrain and consider an immediate attack on that stalled column to try to take advantage of the confusion that would necessarily ensue. MG Hayes had previously ridden up the road to within a few miles of Gettysburg to ‘read’ the terrain and had decided that the area near the Mason-Dixon Line was quite suitable for an attack but less so for defense. It was mainly open agricultural land with some rolling hills and swales, but no real areas that would allow a defensive line. IOW, he could attack and with an element of surprise possibly drive the Rebels fleeing back to Gettysburg.

So at about noon on July 3, the Union counter-attack commenced. MG Caldwell’s Division of 2nd Corps formed up and surged north bracketing the road. They crashed into Johnson’s Division as it waited to understand what had happened a short time ago. The rest of the Corps mobilized to support the First Division but they weren’t needed. Caught by surprise, out in the open and with no cannons in place to support them, the Rebel line broke and ran – practically all the way back to Gettysburg.

Just in case, this impromptu attack developed into a true battle, Meade immediately sent for the 6th Corps to move up closer to Taneytown as both a protective cordon and a reserve force. After only a few hours, however, MG Caldwell ordered a stop to his attack. The Rebels were running away faster than he cared to pursue them. He, too, did not want to advance too far away from his support / reserves. He bedded down his men just inside Pennsylvania and doubled the picket line. The Corps Commander then leapfrogged his Third Division past the Second and had them occupy the terrain that the First has abandoned. By nightfall, 6th Corps was deployed in a tight arc around Meade’s HQ just behind 2nd Corps.

Meade’s next chess moves were designed to strengthen his line. In the morning, one division would need to move up on 2nd‘s the right flank and 5th Corps would need to extend its lines west to marry up with them. The shift of 6th Corps left 5th Corps a bit too isolated on the right near Littlestown so he ordered 15th to move to the area vacated by the 6th.

12th Corps would move north off the road to Emmittsburg and into the open ground in such a way that they provided a link to 2nd Corps on their right and Sickles on their left. They were just inside Maryland. He checked to be sure that the newly arriving 13th Corps was soon to be just to the south of Emmittsburg, a position from which they could support either Sickles or Slocum; possibly both if required.

His next series of telegrams were to assess the status of 7th Corps as it converged on Hanover.

Part 3: a Face-off

America’s Birthday dawned with a somewhat different configuration of forces. The bulk of the Union cavalry was poised mid-way between Littlestown and Hanover. Stuart’s presence at Two Taverns had halted their movement eastward as they might be needed to support against an attack on the 5th Corps.

Otherwise, Meade was quite happy with his position. Reports of Pickett’s presence in Fairfield (prior to his cutting the telegraph lines) suggested that Longstreet’s other divisions must be near Emmittsburg but no contact had been reported. 13th was now just below Emmittsburg able to support either of the nearby corps.

His next major decision was if and when to launch the 7th from Hanover. Were there few enough troops near Gettysburg for such a flank attack to have a good chance of success? Where might Lee himself be? A diversionary attack by 5th Corps might be needed to pin down or draw Hill and Stuart away from Gettysburg as they were the closest units that to circle back to entrap the 7th. With Longstreet to the SW, the biggest concentration of forces in or near Gettysburg would seemingly be Ewell’s Corps.

It was just over a 20-mile straight line march from Hanover, but Meade anticipated that they could accomplish at least half of that without being detected. The only real intersecting road ran from the south out of Two Taverns. That mid-point would be where they would be the most vulnerable to Stuart’s cavalry if it became aware of it presence. He’d need to position a blocking force of cavalry and artillery at the crossroads at Bonneauville PA to protect the 7th‘s flank and then rear as they moved on to Gettysburg. If that blocking force could be in place by evening, the flank attack on Gettysburg could commence as early as the morning of the 5th. He set that corner of the chess board into motion. Purely as a precaution, he ordered his Railway staff to move trains to Littlestown for the possibility of ferrying 15th Corps in a looping attack via the rail line to Gettysburg. He did not believe that using the rail line was practical for the movement of the initial attack force. He did not think that he could concentrate enough troops quickly enough by rail to launch the attack. But as either an exploiting or (heaven forbid) a rescue force that was the fastest option. G-Day was set for mid-afternoon, 5 July.

Meade did not have enough confidence in Sickles to hand him a leading role on the left flank. Even though Emmittsburg might be under threat by the infamous Longstreet, Meade was loathe to do any more than await the Rebel move there. He was even fully comfortable with pulling that entire flank closer to Taneytown. Even if that meant abandoning Emmittsburg rather than sacrifice those corps to Longstreet.

For his part, Longstreet was left brooding a few miles SW of Gettysburg. His cautious advance down the road to Emmittsburg had so far yielded no contact. The sheer fact that Anderson had pulled off a magnificent victory and that Ewell was credited with routing the Union line while his troops were still walking east, irked him to no end. Even that Pickett was living it up in Fairfield while Hood probed for Union pickets did not sit well either. Even before he received word of Johnson’s death, he was en route back to Lee’s HQ. He walked in to find Lee in deep discussion with both Ewell and Stuart who himself had cycled back from his left flank position content that nothing would happen overnight.

Lee had had high hopes that Longstreet could quantify the size of the Union force in and around Emmittsburg. Longstreet’s lack of any new input was more than frustrating. What exactly was Meade up to? He knew little more tonight than he knew last night about the strength and alignment of the Union forces = next to nothing! Johnson’s loss weighed heavily but was over shadowed by the darkness that he was peering into to the south. Even Stuart had failed to encounter any infantry on that flank. Meade had to be in the center of his line near Taneytown, but there was no way to get to him. Only 12 miles away and yet so far! Was there really any bold move he could make to tip the scales in his favor?

The most obvious move – hardly a bold one – was to have Ewell renew the attack towards Taneytown, perhaps even supported by McLaws from the west and Anderson from the east traveling overland. But Lee had no concept of the depth of the Union line behind the Second Corps. What might be between them and Taneytown? One would have to assume that Meade would not allow them to sit on the Mason-Dixon Line with no flank support. Who was out there? Did Meade even know that Pickett was swinging in from the west? Could Hood hold the Union forces’ attention while Pickett outflanked them?

Too many questions; absolutely no good answers! It was a long night!

Part 4: Counter-attack

Throughout the night regiments of 7th Corps moved as stealthfully as possible towards that important cross roads with cavalry screening to the left leading three batteries of mobile artillery. Once the cannons were in place that morning, the 7th began its run the last 10 miles to Gettysburg. As they reached the outskirts of town, they placed artillery on Benner’s Hill and sent a brigade to try to crest Culp’s Hill. Although it was a dominating peak in the real battle, it was far enough to the rear of Lee’s line not to be of concern and was left unoccupied!

But there wasn’t much for the scouts to see. Camped along the Taneytown Road were some remnants of Ewell’s Corps, but no other combat troops were in evidence. The streets of the town were crammed with wagons of all descriptions. There were still some groups of Union prisoners in the strip of land just to the south of the town, but mostly there were cattle and draft animals grazing there.

The vanguard of 7th Corps slipped into the mid-town area along the Hanover Road and more or less quietly began rounding up the wagon masters and support personnel. They formed a cordon and began sweeping south. A few slipped around the SE tip of the town and freed the Union prisoners and spirited them away. More troops gathered on the east side of Culp’s Hill out of sight of the infantry then in mid-afternoon they swept around to the north and south charging into the valley where Ewell’s men were milling about. They were so confident of their position that they had posted no guards or pickets.

No one had any idea where Lee might be. Special squads had been designated to search for him or at least his headquarters but no reports of success were being received.

They had left all of their wagons in Hanover so their support personnel and wagon masters were now ferrying captured Rebel supplies back in that direction. One group was headed back up to Carlisle with the wagon-loads of supplies that Ewell had carried away. High on their movement list were ‘war supplies’ like gun powder and ammunition. Not that they were needed but to deny them to the enemy. Other items like food were left to be ‘claimed’ by the townsfolk who were already reclaiming much of the items that had been ‘bought’ with Confederate script.

By dusk, the riflemen of the entire corps was positioned on the hill running south from the cemetery with the new Rebel prisoners having been herded into the marshy area at the southern tip of Culp’s Hill. They waited there, facing south and east overlooking the two roads that converged there, just in case any troops returned from their excursion south.

Part 5: Breakout

Lee had moved his command staff a few miles south of Big Round Top in the rear of Ewell’s Corps. He wanted to closely manage his break through attack of the Union 2nd Corps. At dawn, Early would begin a movement to contact with Rodes offset to his right in echelon. At the same time, McLaws and Anderson would detach from their respective corps to the west and east moving in to support Ewell.

One of the favored tactics of that era was to attack the point where two different units met. The division of command often made it easier to punch a hole in the line at such a junction. Lee had no way of knowing it, but as Rodes followed Early, his right flank hit just such a meeting point between the 2nd and 12th corps. Early hit the center of the 2nd Corps line and met stiff resistance.

The fighting was taking place in open fields with little in the way of defensive positions. It became a classic set-piece battle of maneuvering regiments which, viewed from the clouds, would have looked much like a chess board. Except that the chess board was filled with pawns. Opposing regiments were intermingled; the more successful soon finding themselves isolated among enemy units. There were no rooks or bishops nor any knights to add punch to the battle. There was, however, the queen of battle = the artillery.

BG Hunt, the Union commander of Artillery, had spent a long day moving and positioning his reserve artillery in support of the Union position. Every available hillock bristled with cannon barrels. He had managed to provide coverage to those points on the flanks of 2nd Corps where they abutted the 12th and 6th Corps. The lack of a clearly defined Union defensive line and the subsequent intermingling of maneuvering regiments complicated the job of the battery commanders, but once Rodes’ lead elements punched through the junction of 2nd and 12th, they came under withering fire. As Rodes’ reserve brigade was moving to exploit that breech, long range artillery hit them hard was well. Slocum’s 12th Corps was the other of Meade’s available troops that was only a two-division corps. But Slocum had held back Lockwood’s 1800-man brigade as a reserve and he ordered them in to close the breech. Likewise, BG Hayes (newly in command of the 2nd replacing Hancock) was able to maneuver another reserve brigade in that direction for support. Almost as fast as it opened, the breech was closed with many of Rodes’ men trapped behind the Union line.

McLaws arrived too late to influence that corner of the battle field so he settled in to await orders. On the chess board, this clash played out much as had the early afternoon of Day 1 of the actual battle with charges and counter-charges shifting the areas of control back and forth. As units disengaged and separated, they would be hit by volleys of cannon fire until they could withdraw out of range or into a swale. It was akin to a barroom brawl; the artillery breaking chairs over their opponent’s backs.

The junction of the 2nd with the 6th Corps to the east held fast. Even the arrival of Anderson’s 7000-man division had no appreciable effect. By mid-afternoon, both armies had separated and a lull settled over those plains.

Lee tried to maneuver McLaws closer to the Taneytown Road but the scattered carnage of Early’s Division inhibited their movement. Long range artillery continued to harass the area on either side of the road. Mclaws could never get aligned and organized enough to make a second assault.

Then Lee received the shock of his life! As he sent back word to bring up ammunition, those messengers that returned brought news that they had been fired upon once they passed north of Big Round Top. They never got to the city to deliver their messages. There would be no resupply of ammunition or anything else!

Lee immediately sent an order to Stuart to have him reconnoiter the situation at Gettysburg. It was mid-evening that he received the news that it and his supplies were in the hands of the Union. Now he was truly an island of the Confederacy; a desert island! It was time for desperate measures. He ordered Stuart to move to Bonneauville to attempt to stem the outflow of wagons from Gettysburg. But nothing could be done until the morning of the 6th. Stuart’s lead elements blundered into the blocking force that Meade had positioned exactly to counter such a move. While the horsemen were able to escape with few casualties, any movement north was interdicted.

That clash was a clue to Meade that Lee understood his predicament. So he ordered to trains to carry the first troops of 15th Corps to Gettysburg via Hanover and Oxford. Those trains could then move even more of the captured booty back to Oxford as they shuttled around. By the evening of the 7th of July, he’d have the better part of two full Corps at Gettysburg. The Army of Northern Virginia was the meat in his sandwich!

There had been more maneuvering going on the 5th of July. Even as McLaws shifted left, Hood was to launch a diversionary probe towards Emmittsburg. Meanwhile, Pickett was ordered to advance towards that city from the west. He was to pause and wait word from Longstreet as to whether or not advance. The collapse of the main attack thwarted any assault on Emmittsburg and Pickett had to withdraw back towards Fairfield so as not to become isolated with no hope of support. Nothing had gone Lee’s way that day!

The Army of Northern Virginia wasn’t quite surrounded but it was close. Trapped in a narrow band along the Mason-Dixon Line; cut off from re-supply; out in the open with no defensive position or shelter, they were in dire straits. But there was still hope. Behind Pickett, there was pass through the South Mtn back to the route he had taken north. If he could push his army to the other side of that pass, he’d have not only a respite but a defensible position at the pass to hold Meade at bay.

Part 6: Abandonment

Lee had Pickett move in closer to Emmittsburg in a blocking position. Then he began to shift all of his chess pieces west aimed at that pass. There were no roads to follow so going was slow at first, but the men pressed on knowing the result of failure.

Hill’s Corps had the longest trek. They had to parallel the Union line the entire way. A straight line distance of about 15 miles. He made it slightly longer by arcing away from the Union line and skirting just beneath Big Round Top. Stuart was given the unenviable task of rear guard. He needn’t defeat the enemy, just delay them long enough to allow the rest of the army to escape.

Most of this movement of well over 50,000 men took place that night. No food, little water, low on ammunition but desperate to see Virginia again, the Rebels trekked west. Hood made a short march west then set up a line paralleling the Fairfield Road. He and Pickett would try protect the rest of the Army as it passed through to the Fairfield Road. Once there, they’d be relatively safe and could slide through the mountain pass unhindered. There were few wagons or ambulances to carry the wounded, so if you couldn’t walk you were left behind.

The Army of Northern Virginia that made the trek back to Virginia was reduced roughly in half. Combat casualties accounted for about half of those losses and prisoners the other half. Even more devastating was the loss of all the food, supplies and equipment that they had brought north or acquired there. The threat of starvation had been a factor in deciding on the invasion. Now that was an even greater likelihood. [ see Sections 1a and 1f] There was little food and fewer war supplies to greet them on the other side of the Potomac.

Would Meade move to attack to destroy the wounded Army of Northern Virginia? That’s a tale for another installment.

Part 6: Escape

Meade considered counter moves, but ultimately decided to conserve his chess pieces. He could have advanced 13th Corps to block the exit route. But they were his least experienced unit having had little in the way of combat while guarding WASHDC. He was afraid that they would either break and run, or worse, get mauled by the Rebels. The determination to get back to Virginia was strong and he was not sure 13th Corps could stop them alone. That move would also isolate Sickles possibly exposing him to an attack by Pickett. He refused to sacrifice any more men even to stop Lee’s escape. Lee had lost a major portion of his army and almost all of his supplies.

And yet, the war would continue!