If we concede the fact that Stuart does not ‘return to the fold’ until the afternoon of 2 July, could his 6000-man cavalry have been better utilized? By the time of his arrival, four of Lee’s nine divisions had been battered into a state of military ineffectiveness. Ewell’s three were out of position to do much to directly support Lee’s Day 3 plan. Anderson’s Division was bloodied but not battered and only Pickett’s had yet to fire a shot.

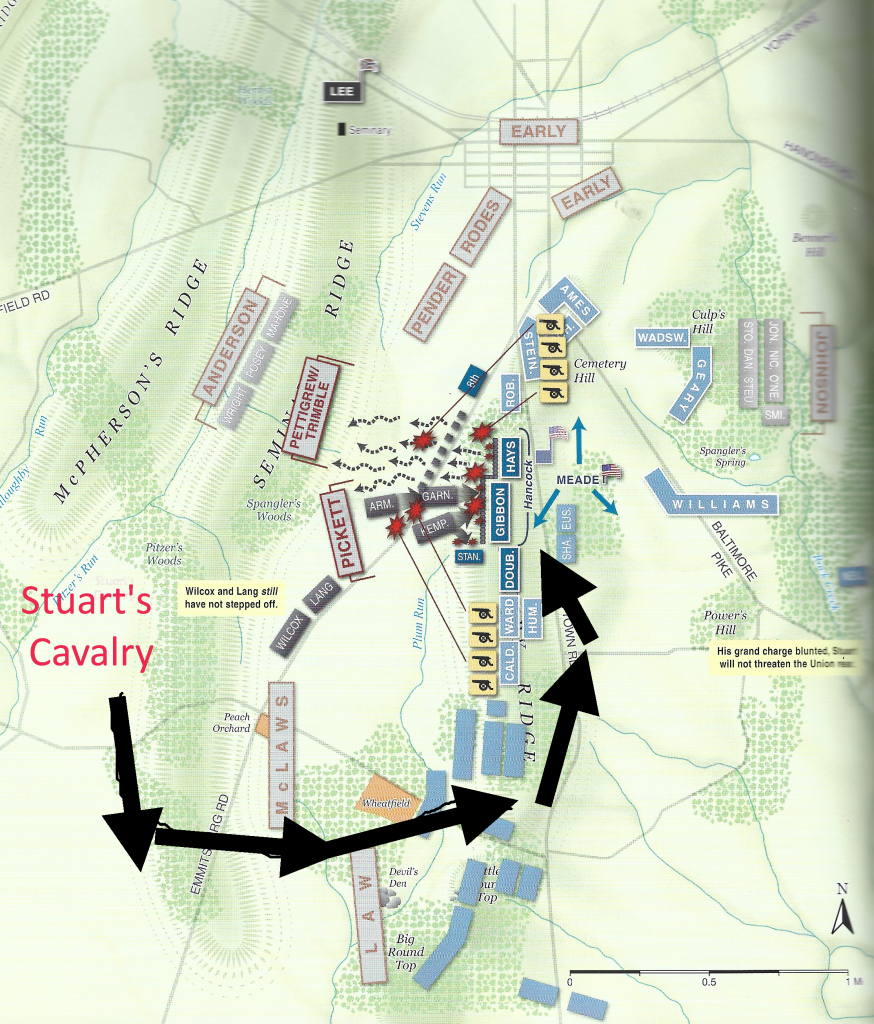

As it was, Lee assigned Stuart only a supporting role for Day 3. He was to launch a diversionary attack on the lightly defended Union rear and reserve area along the Baltimore Pike. On his right flank, Johnson would renew his attack onto Culp’s Hill – again mainly a diversion. Both were designed to tie up Union forces that might otherwise shore up the Union center where Lee was sending Pickett.

My WHATIF here is why don’t Lee add Stuart’s 6000 to Pickett’s 5000? Instead he cobbled together about 5000 from Hill’s Corps most of whom were now under new commanders replacing those wounded or killed.

As other of these ALT Hx analyses will show, Lee had no units that could have possibly exploited any success that Pickett might have had.

Let us suppose that Lee positioned Stuart’s cavalry at the southern tip of Seminary Ridge. They could have charged up the Emmittsburg Road and followed Pickett’s path. In a matter of minutes – remember it only took Pickett about 20 minutes to cross the valley and reach the wall – they could have been at the throats of the Union defenders with swords swinging and pistols blazing. The shock value of the sudden appearance of four brigades of cavalry would surely have broken the spirit of the Hancock’s men.

An alternative strategy would have been to pre-position them behind Rodes’ Division on the SW corner of the city. At the initiation of the attack by Pickett, they would ride behind Pender and swing east. This would place them in front of Trimble. They could have been leaping over the low stone wall before the Union artillery had any chance to re-aim their guns. In this way they would have drawn much of the attention away from Trimble and Pettigrew. I’d propose that this would have allowed those two forces to successfully cross Emmittsburg Road and then reach the slope of the ridge. Since they had a slightly shorter march, they’d have arrived before Pickett. Again, this may have drawn fire away from Pickett’s left flank allowing a more successful advance.

In such a scenario Staurt’s men would be the punch and the infantry the exploiting force. It is most likely that the cavalry would have had to sacrifice itself on the wall to allow the infantry to advance to the wall. But that may have been worth the expense. If the cavalryrmen or the infantry could have penetrated as far as Ziegler’s Grove, they may have been able to establish a foothold to operate from. All said, I fully believe that Lee had more and better options than he conjured up to use against Meade in those crucial hours.

I still contend that I fail to see whatever Lee saw in throwing 10,000 men at the Union line. Getting there was hard enough, successfully exploiting any breech was quite something else.

See the description of The Saddle in Section 30h as to how the terrain may have aided Stuart in such a maneuver.

Regarding Stuart’s cavalry force, even though he technically had around 5500-6000 men, in reality he probably had no more than 3500 effectives at best due to the long ride. His force was tired from the march and needed rest (which he didn’t get). That’s part of the reason why Gregg was able to blunt him in the Day 3 cavalry fight in the rear.

However, I would also point out that there was another good reason why Stuart wasn’t utilized to directly support Pickett. His command would have been massacred if they charged the Union center. Rifle volleys and canister fire would have wrecked Stuart’s force before they even got close to them. See what happened to Kilpatrick’s Union cavalry (focus on Farnsworth) on the far left of the Union line on Day 3 (around the Round Tops) for an example of why cavalry didn’t charge steady infantry formations (long story short, the Union cavalry was hammered pretty badly).

On a side note, I’ve enjoyed reading this extended essay. It’s been well thought out.

I take the view that given the choice at firing at fast-moving cavalry or Pickett’s mass formations, the Union troops would choose the latter.

I DO appreciate the imbalance of massed volley fire against cavalry, but the same generally applies to massed infantry formations.

I STILL hold that even at 3500 ‘effectives’ Stuart’s addition to Pickett’s infantry would have been a better choice than either of the cobbled together formations on Pickett’s left that day.

Stuart’s men being utilized as a dismounted infantry force is an intriguing concept and I’ll admit that I never considered the possibility. In a dismounted role, then Stuart would have had about 6000 effectives. Even regarding the fact that they were armed with carbines at best (and some were pistol/sword armed), it might very well have been a better force than Heth or Pender’s divisions that took part.

Another interesting note is regarding Mahone’s Brigade of Anderson’s Division. During the 2nd day, Mahone was supposed to attack Cemetery Ridge, but for some reason, held back. His excuse was that he was told to hold position, but that was definitely not the case. Inexplicably, he retained command of his brigade after the battle. Mahone was held back on Day 3 to protect the artillery, but I think he would have been much better utilized supporting Pickett (Mahone’s brigade numbered 1500) or even attached directly to partly compensate for the loss of the two brigades Pickett left behind in Virginia. Such a move would have given Pickett a more robust 7000 or so infantry in addition to the other divisions. Add Stuart’s force of 6000 and that would have been a fairly formidable number for the assault (well over 20,000).

While it would have given the attack more of a chance to succeed, I’m still unsure whether it would have mattered. Sedgwick’s VI Corps of anywhere between 13-16,000 men was a very strong reserve force which would almost have certainly reinforced Hancock’s 5,000 men at the point of attack (not to mention all the artillery around the area). It certainly would have been a more close-run affair, but I do think the outcome ultimately would have remained the same, just with much heavier losses on both sides.

Ultimately, it seems hard to understand why Lee even chose to mount a campaign northwards at all (other than gaining a windfall of supplies for the army) given what was happening in the western theater. Vicksburg was far more strategic than anything Lee could come up with and even if he could have somehow ‘won’ at Gettysburg, the entire exercise of the invasion was moot by the time of the battle. Vicksburg surrendered on July 4 (with Port Hudson following five days later) and the Union gained control of the Mississippi River. Grant’s 70,000 effectives and Banks’ (he was besieging Port Hudson) 30,000 would have been more than sufficient to deal with Johnston’s army in Mississippi (30,000) and leave more than enough to rail the rest back east (although it would have taken some time to do so).

Rosecrans in Tennessee could even have been ordered to detach a division to support Grant and that would have still left him with almost 70,000 to face Bragg’s 50,000. As such, Grant likely would have had a second army staged somewhere in Pennsylvania (around Harrisburg?) by the end of July (over 50,000 veteran troops augmented by thousands of militia).

The much reduced ANV of perhaps 55k would have been trapped between two good-sized armies (the AoP was still at around 65-70k strong after Gettysburg). Either way, Lee would have been forced to withdraw without accomplishing much. As far as inducing the north to submit due to political pressure, it was the wrong year. Union elections wouldn’t be until November of 1864, well over a year off. Lincoln, despite being pressured, would have almost certainly ignored the pleas to begin negotiations.