When one reads or writes an account of war or a specific battle, that account is almost universally about the tactics and actions taken; the exploits; the bravery (or sometimes cowardice) of the participants. Such accounts often include details such as the enumerations of casualties, but rarely more. We tend to be more interested in how a soldier earned a medal than the fact that during Pickett’s Charge the 38th North Carolina Regiment suffered 100% casualties.

To form the accounts of these battles we use original texts. Official records (after action reports) tend to be very boring accounts of the basic event. We turn to personal memories, memoirs, diaries and personal letters to fill in the details and humanize the event. But throughout history there are other records that tend not to be included in these sweeping accounts of heroism. These are the logistical records. Reaching back thousands of years, the Romans keep records of just about everything; the Greeks less so. During the two world-wide wars, the Germans kept meticulous records; then destroyed many as the tide turned against them. Embedded within every military organization are the “bean counters”. By and large, these men were good at their jobs; they counted and recorded those counts. Throughout history, they often did so in very organized ways: they created and completed forms, often on a daily basis. Adjutants counted people (Morning Reports), Armorers counted weapons, cooks and commissary officers counted barrels of food, etc. Such reports were usually made in very uniform ways and filed on a very regular (daily?) basis. Hence armies would amass crates full of records – many if not most unread! And so too, for the Battle at Gettysburg. There are archives of such records that for the most part go unread and unreported. In his book, Retreat from Gettysburg: Lee, Logistics and the Pennsylvania Campaign, K.M. Brown delves into such records and in doing so provides us with a very unique perspective on this event.

We learn, for example, that in addition to the two grand strategies laid out in Section 1a of these essays: to win a battle on Union territory and possibly to win the war if not militarily then via a negotiated settlement, Lee had a third — perhaps even more important objective: to avoid starvation.

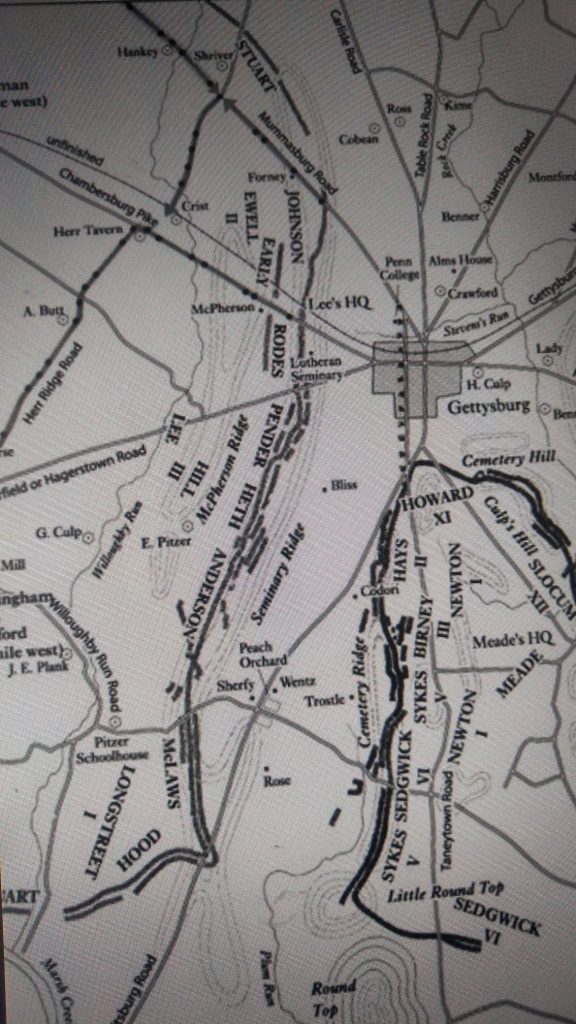

As noted in Section 1a, much of the fighting over the first two years of the war had taken place in Northern Virginia. As armies of 100,000 men marched back and forth, they drained this region of just about everything. Brown tells us that as they came out of the winter stand-down in 1863, the Army of Northern Virginia (ANV) was in dire straits. First, they had been pushed quite far west away from Richmond, lengthening their supply lines. A drought in the summer of 1862 had decreased the harvest and was being felt heavily by the spring of 1863. Beyond his military and political plans – perhaps even more importantly — Lee was looking north to the Cumberland Valley as a source of food for his men and draft animals as well as basic supplies of all kinds.

The depth of the supply shortages is reflected in official CSA records that show that LTG Ewell was not issued much in the way of food stuffs as he crossed the Potomac. As the vanguard Corps, he was expected to plunder the countryside to feed his men and horse/mules. One of the reasons he was so far north at Carlisle was that it was a major Union Supply Depot.

K.M. Brown reminds us that an army does indeed travel on its stomach and that it takes vast qualities of supplies of all kinds to keep the machinery of war working. Lee needed every possible class of supply he could gather. Partially because of the lower level of industrialization of the South, any and all sorts of manufactured goods were in short supply in 1863.

But Lee also understood people and showed concern for those who might ‘suffer’ as a result of his need for these ‘necessities’. He issued specific orders prohibiting what might be called “plundering and pillaging”. Any soldier caught stealing was to be punished severely. While he intended to gather every possible item of any use, he would not allow the army to rape the land (nor the people). Only ‘authorized personnel’ could procure supplies. These were generally limited to Quartermaster, Commissary and Medical Officers. Every unit, however, had scavenger parties that would reach out parallel to the route of march looking to gather food (mainly) to feed the unit for the day. Lee ordered that all such supplies (with certain exceptions) be ‘paid for’. The problem was that the CSA currency or “military certificates” issued as payment were essentially worthless in the North! It was a common occurrence for the designated officers to meet with a town’s leadership and demand that that town provide a specific list of supplies for which ‘payment’ was then made. It wasn’t so much a contribution to the CSA war effort as it was extortion, but it was legal under Lee’s orders. Exceptions were made however if it was discovered that items were being withheld or hidden. Such an act would then permit the “authorized personnel” to outright seize or ‘impress’ such goods without recompense!

JEB Stuart’s plunder:

When MG Stuart finally reported in to Lee’s HQ in the late afternoon of 2 July, he reportedly handed over to LTC Corley, the Chief Qtrmstr, 150 wagons and 900 mules that he had plundered from the Army of the Potomac. Perhaps this was one factor that seemed to ameliorate Lee’s response to his long absence.

While Stuart was Lee’s senior, favorite and likely best cavalry commander, he often assigned special tasks to BG Imboden and his cavalry. Just before the northern incursion, he had dispatched them into the Shenandoah Valley to forage for supplies especially cattle and horses. In the aftermath, it fell to Imdoden to command the vast wagon train of wounded and captured supplies back to the safety of Virginia. During the northerly movement, he was in charge of the vast herds of cattle, sheep and pigs that fed the army. Brown also informs us of a rarely acknowledged fact: Imboden’s unit included a large number of slaves whose primary job was to tend to the herds and the horses and mules of the supply wagons.

Horses and mules:

One cannot overstate the importance that draft horses, mules and to a lesser extent oxen were to the armies of this era. As many as 30% of the assigned strength of the armies travelled in the vast logistics trains. Throughout the spring of 1863, these draft animals suffered hunger and deprivation alongside their human masters. A lack of proper feed and fodder led many of them to become ill. A draft horse can easily consume 10 pounds of feed (mainly corn) in a day. By June, the ANV barely could provide three! Corn was a major crop in the Cumberland Valley of MD & PA. It was nearly as vital to the army as ammunition.

In actuality, the road south from Chambersburg PA back into Virginia was 170 miles long and, unusual for the era, most of it was macadamized. Most of that road was hosting the wagon masters and their teams. Supply wagons and artillery were strung out between the marching infantry formations and ran a continuous circuit back to Virginia. The other item that the ANV was in dire need of was shoes! The myth of the AVN going to Gettysburg in search of shoes has been thoroughly debunked, although a large percentage of the soldiers were indeed barefoot. But horse-shoes or even the steel to make them or the nails to secure them were also in short supply. This was especially problematic for those animals walking on the macadamized roadway. A lame horse is a useless horse but still needs to be fed (or eaten).

A Bountiful March:

As noted above, it was common practice as a unit entered a town to present those townsfolk with a ‘shopping list’. Failure to agree to this extortion could result in punishment of individuals or the burning of buildings. K.M. Brown provides us with a list derived from records of what was demanded from the fairly large town of Chambersburg PA by Ewell’s Chief Qtrmstr :

5000 suits of clothing to include hats, boots or shoes; 100 good saddles and bridles; 5000 bushels of corn or oats; 10,000 pounds of shoe leather; 10,000 pounds of horseshoes and 400 pounds of horseshoe nails; 6000 pounds of lead; 10,000 pounds of harness leather; 1000 curry combs; 2000 pounds of rope; 400 pistols and all the gunpowder that was available.

In addition, the Commissary Officer demanded:

100,000 pound of ‘hard bread and 50,000 loaves of fresh bread; 11,000 pounds of coffee; 10,000 pounds of sugar; 100 sacks of salt; 30 barrels of molasses; 500 barrels of flour; 25 barrels each of vinegar, beans, dried fruit, sauerkraut and potatoes.

All to be loaded on to wagons also provided by the towns people; all ‘properly paid for’ with CSA IOUs redeemable after the war was over. They also left with every horse, mule, cow, sheep and hog they could find. Although outright looting was prohibited, one individual seemed to have been singled out. K.M Brown describes how the sawmill, furnace, forges, mills and storerooms as well as the offices of one Thaddeus Stevens a good citizen of Chambersburg, but known ‘radical Republican’ were burned to the ground but not until they were stripped bare of any and all useable materials such a bellows and pig iron. Also removed from his stores were thousands of pounds of bacon, corn and molasses and all of his horses and mules.

At Wrightsville, MG Early’s officers ‘confiscated’ over $25,000 dollars in Union currency as well as thousands of hats, shoes and socks. Even as Longstreet’s Corps was the third to pass through Chambersburg, they reportedly came away with 2400 horses and 1700 cattle. It is also said that Longstreet demanded “rations for 60,000 men”. When the town’s officials stated that no such amount of food was available since his was the third CSA Corps to pass, Longstreet’s men simply looted every store and storehouse they could find, stripping them bare. “Receipts” were provide for goods so procured. Surviving receipts list all manner of goods to include books and pencils, pens and ink, paper and envelopes, tools and scythes, wood and nails, anvils and augers, needles and thread!

Ewell’s ‘procurements’ from the Union Depot at Carlisle were never properly recorded. Needless to say, his ‘takings’ were cut short by his recall to Gettysburg. Most of those wagons followed Johnson’s Division to Cashtown before continuing south. One record suggests that they carried 42,000 pounds of feed corn and 49,000 of hay but his true (unrecorded haul) was likely in military hardware and uniforms.

Much of this ‘bounty’ was not taken to Gettysburg. Rather, it was re-directed south causing something of a traffic jam on the highway and delaying the arrival of MG Pickett’s Division that was providing the rear guard. CSA records suggest that well over 50,000 head of cattle, 35,000 sheep, 20,000 horses and tens of thousands of hogs were sent back across the Potomac as the ANV moved through the Cumberland valley. ‘Newly procured’ horses and mules were usually pressed into immediate service, while the tired, sick, or wounded animals were sent south.

On the CSA side they had one other resource that the Union lacked: slaves. Although no records survive (if they were even kept), it is estimated that Lee had between 6 and 10 thousands slaves in his ranks. Most were there to do manual labor like erecting and dismantling tents; cooking food or doing maintenance on the wagons. Others were assigned to look after the large herds of livestock that accompanied these armies on the move. In addition, most CSA officers and even some enlisted were attended by their own personal slaves. Should his ‘master’ be wounded, he would care for him in the medical facility. Following a battle, large numbers of slaves would be seen carrying lanterns searching for their dead or wounded ‘masters’. One side-effect of such activity is that slaves would “suddenly find themselves among the Union lines”!

By 3 July, the ANV had a new logistical problem: POWs. They had captured 5-6000 Union soldiers and held a handful of local civilians as well. They were loath to free the civilians who had “seen too much” behind the lines. The Union prisoners were held in two large groups; one guarded by Heth’s men west of the city and the other controlled by Longstreet to the south and west. Lee himself is said to have “bristled” at having to feed so many to say nothing of dozens of wounded in his hospitals. He made overtures to have a prisoner exchange, but Meade was having none of that. Better to make Lee have to deal with that burden. Their senior officer was BG Graham who had been captured in the Peach Orchard debacle. Lee had about 1500 marched north on the road to Carlisle and released there.

A Pyrrhic Bounty?

BG Imboden’s huge wagon train of wounded departed the Gettysburg area late on 3 July, soon after Pickett’s failed attack. Its primary cargo was thousands of wounded and hundreds of Union POWs. But included in it were hundreds of wagon-loads of plundered supplies. Feed corn and hay and other varieties of grain such as barley and rye were also in great demand. Such could be stored almost indefinitely to nourish the huge number of draft animals in the ANV.

Another commodity that was dispatched back to Virginia were (former) Freemen. Liberated slaves found in the path of the march north were “returned” to their slave status and sent south. No accounts seem to have survived the war that would enumerate just how many slaves were ‘re-claimed’. Many of these were pressed into service to move the plundered livestock southward.

It is also fair to say that once word of this action spread, many Freemen packed up their families abandoned their farms and lives and moved as fast and as far away as they could. Many never returned.

In short, Lee’s major goals of ending the war were not achieved, but he did manage to feed his army and store provisions and military kit for many months to come.

The Union Side

When Meade finally made the decision to push his entire Army to Gettysburg, he also made some logistical sacrifices. In order to keep the roads open for his seven Corps, he held the vast majority of his wagons in and around Westminster. Tons of supplies were arriving there daily but little was leaving. Each Corps had taken with them the bare minimum of food stores and tentage; concentrating on ammunition and medical supplies.

By the time Pickett’s attack was repelled on Day 3, the Army of the Potomac was hungry, tired and low on ammunition. This played a large role in Meade’s decision not to pursue the Army of Northern Virginia into the Cumberland Valley.

Meade needed to get food and fodder from the Westminster area as well as the repair wagons with forges for the blacksmiths to repair the many wagons and artillery caissons that had been damaged in the Day 3 pre-attack bombardment.

Day 4-5 weather

It is not exactly logistics, but by the early morning hours of 4 July, the weather played a major role. Lee had shifted Ewell’s three divisions to the west side of town. They formed a long skirmish line complete with breastworks running south to north just in case Meade decided to counter-attack. Just as the initial wagons started to move west and south as part of the retreat, the heavens opened up. It rained heavily for over 12 hours. This naturally slowed the exodus but also helped to mask it.

Once they knew that Ewell had shifted, a Union Signal unit returned to a steeple in the town that it had occupied on Day 1 and began to report on the ANV’s movements. But they were severely hampered by the rain. All they could see and report was that the skirmishers were changing regularly every few hours. They completely missed the thousands of wagons leaving the area. The rest of Lee’s exodus was blocked by Seminary Ridge. To compound the masking of the movement, Lee used one of his favorite tactics. As Ewell’s men began their retreat, they set fire to their breastworks, thereby, further masking their movement with smoke.